Jade Boyd (2017) (Re)visualizing women who use drugs, Visual Studies, 32:1, 70-80, DOI: 10.1080/1472586X.2017.1286948

Goodfellow, A. (2012). Looking through the learning disability lens: inclusive education and the learning disability embodiment. Children’s Geographies Vol. 10, No. 1, February 2012, 67–81

Boyd expresses quite directly the importance of the ethical commitment in conducting personal visual ethnography with participants, despite the obvious value such research may have to researchers and organizations like VANDU. In particular, researchers must not only have the right motivations, they must also become supporters and allies of the social justice mission, a subjective action that may be the antithesis to the conventional norms for objective research. As Boyd states:

“The VANDU guideline, ‘Research and Drug User Liberation’, states that ‘researchers can play a positive role when they act as supporters, allies and partners of this movement for liberation’ (VANDU 2014). However, they note that ‘research is political. . . The relationship between the researcher and the researched is not in and of itself empowering or liberating. . .’ (VANDU 2014).(71)

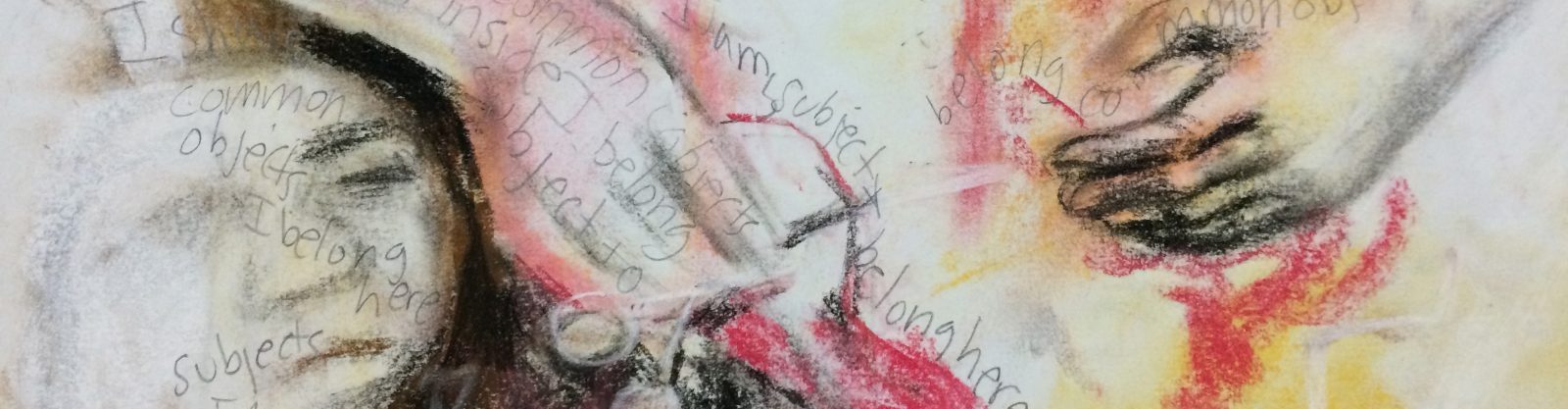

Several ideas that “popped” for me from this piece: Although I am not sure I agree in every case, Boyd recounts that participants should be invited to explain the “visual images they create,” which may not always be understandable to researchers or to readers (72). However, I would qualify this to apply in those cases where, to the best judgment of the researcher, such a practice would benefit the creator of the work, not the reader or researcher. I think such work should never be shared for the benefit of anyone else, unless the participant/creator explicitly wills it. Yet, I may raise this possibility with my students’ work–I expect some of my students would like to speak about the meaning or intention expressed in their work, but some may very well not ever want to nor need they do so.

p.s. The article raises the nefarious consequences of even well-intentioned laws of prohibition (as against drug use). It may be true that drug addiction is not good for your health, and that we should prohibit it, but such prohibitions at the same time not only marginalize those who succumb to drug use but also disincentivize the legitimate need for investment in harm reduction initiatives for those who do not abstain. The law may very well aspire to an ideal, but it may be far from the experience of many in reality. I felt this research methodology acted as an important component in therapy and recovery…in reality.

I have problems with Athena Goodfellow’s article, although she brings up interesting possibilities. For instance, it is interesting to consider….Can special education spaces create nonjudgmental “places,” as suggested by the students themselves, where they can experience no alienation in the special learning methods and accommodations they desire and embrace in their learning, and yet fend off the disabling social stigma that isolates them as alien to the general education classroom? Students indicated that they were aware of both realities, but that they fully embrace the former and suffer the latter. It is also interesting that the students expressed enthusiastically their desire to have adults as teachers who have themselves experienced learning disabilities.

Despite the interesting insights Goodfellow uncovers, what I found most troubling in the piece was the use of probing questions by the researcher to uncover perceptions and feelings of alienation in the student participants. I did not like that. Furthermore, I think very few people would argue against the need at times for precisely these very types of services, including self-contained special education classes. But the arts-based research in this case, though well-intentioned, was I think misapplied in not embracing the need for special education. But rather than directing students to locate their obvious source of pain, perhaps the methodology can direct students through photographs and drawing to identify what it is that gives them power in that experience, what it is that they possess that others never will…. Of course, this is much easier said than done.