Gene’s comments on Dahlia’s and Lamar’s posts, 4/14/19

4/14/19 Gene’s comments on Dahlia’s and Lamar’s posts for this week.

Hello all:

Robert Shreefter emailed me a few days ago to tell me that, due to a family emergency, he had to cancel his visit to our class tomorrow. I am, obviously, saddened by the news. There is a chance Robert may be able to join us before the semester ends, but at this point the chances are, at best, 50-50. There is much to talk about, however, in relationship to the articles that Robert suggested we read (as Dahlia’s post makes abundantly clear). Additionally, Noor – who couldn’t be with us last week because she was at AERA – has agreed to talk about her project. I’m also hoping Gregory, who didn’t get much time to talk about his project last week, can talk a bit more about where he’s at with his project – I’m particularly interested in how his subjects want their work to be shown and what they say about it.

I thought Dahlia’s comments and reservations about the articles that Robert suggested we read were sharp and poignant. I think they bring up many theoretical concerns, and that it is time, now that we only have a few sessions left, to think about how theory frames our own work and goals. We may not have talked about this enough in our class. When you write, Dahlia, about how the children’s art was used not to “just document experience” but to “help process and construct the understandings the kids had of themselves and their surroundings” is that a comment about art as a visual methodology with a specific purpose or intention? How does that relate to arts-based research? Thinking about the article by Wang et al that we read a while ago, are the children’s drawings and collages featured by Robert and some of the other authors for this week an example of “art as research” or “art in research?” And what did you all think about the relationship between the artists and the children in Robert’s articles and the others (that weren’t on the syllabus but available on our Common’s site). I also am curious about Dahlia’s comments of collage as a “stance,” and hope to hear more about it tomorrow.

Putting aside for the moment Lamar’s startling and joyful comment about preparing for his “grandchild,” – something I definitely want to hear more about – I am excited about the progress he is making with his project. Are you moving from “documentation” to “a process of “constructing understanding” (using Dahlia’s phrase) and how do the collective collages and interviews fit into that process? Unfortunately, the link Lamar provided hasn’t yet worked for me, but I know we will all hear the interviews before the semester is over. I also wondered, Lamar, if your Black male students decided, after all, to join the collage-making and how the felt about their drawings after speaking with you.

I need to apologize for this late and brief set of comments. I had an odd day today and am just now getting the time to review the posts.

Dahlia’s Thoughts – 4/15/2019

I have to admit that I had so many feelings pop up while reading the pieces for this week.

I was excited to see how a range of different art forms from poetry to photography to collage to pop up books were used to help showcase the knowledge that kids already brought with them to school. From Paule Marshall’s love letter to the women in her life, to her childhood and to language to the Club Kids crafting magazines, there was a sense of love and honoring of kids. I loved the project where kids created pop up books that connected their own lives to those of famous changemakers because this idea of understanding the dialogue between now and then, between us and them, between what lives in history books and the ordinary moments of our lives is so crucial and yet so rarely touched upon.

But there were a few moments that made me pause. For example, in the piece Learning to Swim in Michigan, Craig Hinshaw writes, ” After reading their books I saw these immigrants to Hiller School in a new and more understanding way. It became clear to me how much all parents want the best for their children.” Part of me wanted to scream. Scratch that. All of me wanted to scream!

Why wasn’t this the assumption of the teacher before starting the project? Why did it take a whole bookmaking project for them to see immigrant parents as holding the same love and hopes for their kids? How could he possibly not recognize that when parents immigrate and sacrifice so much to come to another country, the well-being of their kids is what is on their minds? Why did they need to prove their worth to this teacher? Why wasn’t there the presumption of being a parent who cared?

Clearly the attitude of this teacher – Craig Hinshaw – infuriated me. But then I paused again and realized that maybe I was living in an idealistic lala-land where people actually valued other human beings and gave them the same benefit of the doubt they gave people “like them.” Craig Hinshaw is not unlike many teachers with whom I have worked in NYC – teachers who need evidence of their students’ (and their families’) humanity.

So…since we do live in this world…the importance of combining the arts with the lived experiences of our students feels so much more important. I take this for granted because I have been (oh so) privileged to have attended and taught in schools that saw the diversity of their students as a source of wealth for the schools. That used personal narratives and family histories as a way to create lessons and murals and celebrations. That brought in families as partners.

But I know that this is not the norm, as Robert Shreefter points out in the Borders/Fronteras piece. After all, the big project of American public schools, from the beginning, was to erase the language and culture and heritage of the students who came in in order to Americanize them. So, of course, kids are often taught that school is not a place where their stories belong. What intrigued me about this article was the sense of honor that both the students and the art was given. Their stories were taken seriously and lifted and honored. And art was a way to slow down, to really think through different elements of their experiences from the landscapes of Mexico to their interior landscapes. And then to think through the different artistic elements that could help convey the depth of these emotions. Art was not relegated to the role of just documenting experiences, but was, instead, used to help process and construct the understandings the kids had of themselves and their surroundings.

This is an idea I want to continue thinking through – and playing with…how do we think of art was a way to see things? I am starting to now see that the way I understand collage (thanks to scholar-artists like Gene and Victoria) is not just as a product or even a process but as a stance. As a way of being intentional about the messiness, the layers, the overlaps of life.

Lamar. Ok Post for 04.15.19

My partner and I have been super busy this week preparing for our grandchild (yes, grandchild- no typo) that is entering the world by April 18th and preparing for Canada, so here is my low quality post, sorry!

On Friday, my 30 third grade students split into groups of 3 and made a collage of Hope collectively using 90 different hope drawings and writings from third graders at my school. My co-teacher recorded some of the process in the classroom while I was in the hallway interviewing and recording students one at a time (30 sec or less) share their hopes and drawings. This was strictly voluntarily for the students BUT then I realized that none of my Black boys did NOT want to share their hopes and drawings, so I spoke to them off camera and asked what was up. They said they thought their drawings wasn’t great and elaborate like the others and that they didn’t think what they wrote was important to show to whoever is going to watch the interviews. I hugged them, thanked them for their honesty and vulnerability then affirmed and assured them that what they have to say and what they drew is beautiful, worthy and necessary for the world to hear and know!

Not sure how to exactly present the collages and videos to our class. But I will present them whenever the syllabus says to present them.

Thanks for reading and listening!

Here is a sneak peek of one of the interviews:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1YrEJwbL_M_Zr6KEdLqoLYlax6w-We3Mm/view?usp=sharing

Boyd:Revisualing women who use drugs, Goodfellow: SLD Visual,Comments Luis Z

Jade Boyd (2017) (Re)visualizing women who use drugs, Visual Studies, 32:1, 70-80, DOI: 10.1080/1472586X.2017.1286948

Goodfellow, A. (2012). Looking through the learning disability lens: inclusive education and the learning disability embodiment. Children’s Geographies Vol. 10, No. 1, February 2012, 67–81

Boyd expresses quite directly the importance of the ethical commitment in conducting personal visual ethnography with participants, despite the obvious value such research may have to researchers and organizations like VANDU. In particular, researchers must not only have the right motivations, they must also become supporters and allies of the social justice mission, a subjective action that may be the antithesis to the conventional norms for objective research. As Boyd states:

“The VANDU guideline, ‘Research and Drug User Liberation’, states that ‘researchers can play a positive role when they act as supporters, allies and partners of this movement for liberation’ (VANDU 2014). However, they note that ‘research is political. . . The relationship between the researcher and the researched is not in and of itself empowering or liberating. . .’ (VANDU 2014).(71)

Several ideas that “popped” for me from this piece: Although I am not sure I agree in every case, Boyd recounts that participants should be invited to explain the “visual images they create,” which may not always be understandable to researchers or to readers (72). However, I would qualify this to apply in those cases where, to the best judgment of the researcher, such a practice would benefit the creator of the work, not the reader or researcher. I think such work should never be shared for the benefit of anyone else, unless the participant/creator explicitly wills it. Yet, I may raise this possibility with my students’ work–I expect some of my students would like to speak about the meaning or intention expressed in their work, but some may very well not ever want to nor need they do so.

p.s. The article raises the nefarious consequences of even well-intentioned laws of prohibition (as against drug use). It may be true that drug addiction is not good for your health, and that we should prohibit it, but such prohibitions at the same time not only marginalize those who succumb to drug use but also disincentivize the legitimate need for investment in harm reduction initiatives for those who do not abstain. The law may very well aspire to an ideal, but it may be far from the experience of many in reality. I felt this research methodology acted as an important component in therapy and recovery…in reality.

I have problems with Athena Goodfellow’s article, although she brings up interesting possibilities. For instance, it is interesting to consider….Can special education spaces create nonjudgmental “places,” as suggested by the students themselves, where they can experience no alienation in the special learning methods and accommodations they desire and embrace in their learning, and yet fend off the disabling social stigma that isolates them as alien to the general education classroom? Students indicated that they were aware of both realities, but that they fully embrace the former and suffer the latter. It is also interesting that the students expressed enthusiastically their desire to have adults as teachers who have themselves experienced learning disabilities.

Despite the interesting insights Goodfellow uncovers, what I found most troubling in the piece was the use of probing questions by the researcher to uncover perceptions and feelings of alienation in the student participants. I did not like that. Furthermore, I think very few people would argue against the need at times for precisely these very types of services, including self-contained special education classes. But the arts-based research in this case, though well-intentioned, was I think misapplied in not embracing the need for special education. But rather than directing students to locate their obvious source of pain, perhaps the methodology can direct students through photographs and drawing to identify what it is that gives them power in that experience, what it is that they possess that others never will…. Of course, this is much easier said than done.

Gallery Walk: Student reflections on Student Visual Self-reflections 4.4.19 by Luis Z

I wanted my students to direct the next step of the visual self-reflections practice we began this semester. Thus, students were given the choice today (Thursday, 4/4/19) to either:

a) free-draw/write a second visual reflection which was based on two new prompts Visual Self-reflection #2 (this would be the second in-class visual self-reflection we scheduled this semester)

OR

b) view and give comments on the first visual reflection #1 Visual Self-Reflection Prompt #1, created by students two weeks ago, provided each student gives permission for us to share their reflection.

They chose the latter: I had placed yellow stickies on each desk in anticipation of this so that students could give permission privately to share their work publicly with classmates–on the sticky, they wrote yes/no to share, answered a few other unrelated routine questions I asked, folded the sticky, and dropped at my front desk. I quickly scanned the responses…

They unanimously chose to do a gallery walk, and seemed enthusiastic about doing so. I reminded students that their work was laid out with the visual drawing face up (hence, anonymous).

Attached are copies of the student feedback/comments on their peers’ visual art, the comment sheet attached in the order following the original student visual self-reflection: Visual Self-reflections StudentGalleryWalkCommentaryonThur4.4.19

PROCESS:

In the adjoining empty classroom, I had set each student’s visual reflection on a separate desktop, together with two blank sheets stapled together (the drawing and the feedback sheet were coded). Students were told they could circulate and respond anonymously in writing as they wish to the drawings they viewed at each desk, sharing their impressions, what they would like to say, if they agree, understand, not agree, have advice, etc. etc. I stated that I would like to share their comments with the author of the visual self-reflection, “so be sincere, etc. etc.”

Afterward, we met back in our regular classroom for quick debrief , and then continued on in our lesson.

Some of my reflections of today’s practice:

The primary sentiment that was voiced by many students in writing about others’ work was that they could relate to the feelings of challenge and frustration expressed visually in the work. Others offered some advice, some encouragement, and even some solutions to math problems alluded to.

In the classroom debrief afterward, students volunteered to publicly share their experience of the gallery walk with the class. What was most pronounced with many students who volunteered to speak was their sense of relaxation in knowing that they were not the only ones who were struggling or facing significant challenge. Most sympathized with this , stating in as much the same way that the first two students E and L unequivocally did, that ” …I just felt comforted to find out that I am not the only one feeling like this in the class.” A closing comment made by student S in obvious humor cracked up the class: “I can understand the few happy drawings I saw–when you lose all hope, a sense of euphoria can take over…”

Although I am cautiously optimistic in the benefits of this exercise for my students, I am certain that there was some level of cathartic benefit for students in this sharing with one another. In the climate of a highly competitive college, students can easily presume everyone else is strong academically and thus not feel welcome to share their own struggles or perceived weaknesses.

I also was inspired, perhaps reassured by some students, and it surprised me that it often was the result of seeing some very subtle passing detail in a student’s work…a reticent student’s image of a bulging boundary that is “almost breaking through,” or another student’s images of “the cascading/snowballing effect of one tiny unaddressed question.” I also felt that I saw glimpses of contrary evidence to what I had presumed to be true about students, truths which were not apparent previously from student behavior observed in the classroom: for instance, I was moved by student P’s work reflecting strength and resolve, which was not apparent in the behavior nor in the limited commitment and work I had seen from him previously.

I will want to think about ways I can continue to improve this experience for students:

-to better build upon what we have started (so that it does not become just a “one-shot” fun exercise),

-to establish a momentum so that subsequent exercises naturally evolve in the practice of visual self-reflection,

-to deepen or extend student reflection, perhaps to their study habits and habits of mind that impact performance (perhaps through visual reflection engendered by focused attention on images I submit to them…?)

-to assess possible refinements and/or modifications for implementing this in other first year community college developmental math classes in the coming weeks. For instance, I know I would now plan and set better expectations for sufficient time for gallery walk and commentary, so that students can feel free to reflect and comment more extensively on the work of others. I think I gave the impression that it was a quick scan of the works of others rather than a potential second reflection…..leaving some students to think that perhaps they should only make quick comments.

Lamar. Ok. Boyd and GoodFellow

Readings:

- Looking Through the Learning Disability lens: inclusive education and the learning disability embodiment by Athena Goodfellow

- (Re) Visualizing women who use drugs by Jade Boyd

The two readings provided this week was eye opening. What I got from the Boyd (2017) reading was the process of the community participatory research is just as important as the artistic and research product or outcome. I think about the visual work that I do with my students, and I have to really take a step back and really enjoy the actual process, not just what they produce after the timer goes off. When I do my final collaborative collage project with my students, I am going to live in the moment with them, be present with the joy of collaborative art making, document the process, be human with them, be me while they be them. bell hooks was quoted in this article saying, “That joy needs to be documented. For if we only focus on the pain, the difficulties which are surely real in any process of transformation, we only show a partial picture.” Best quote from the article, “Visual sociologists and other social researchers have argued that ‘art is capable of something which academic work is not’.

Goodfellow (2012) article had my neurons firing in different ways. This quote really resonated with me in thinking about my art project on freedom dreams and hope with my students is, “It important to recognize here is that the participant’s imaginary world is centered upon the enhancement of physical attributes such as being ‘huge’ possibly as a means to redefine him outside of his perceived intellectual attributes.” Imagining is beautiful, it’s freeing, it’s liberating, it’s something that no one can take away from anyone. When we imagine, we are finally in a space where we are free to think and free to live a world without domination and colonization. This reading made me think of the non-binary inclusion and exclusion of Black and Brown children within education. Which brown/black children are accepted and affirmed, and which ones are not, and why? Inclusion and exclusion is not always as obvious and clear as day as gifted classes vs. special education 12 to 1 classes. I wonder in ways which my students feel labeled both negatively and positively, and if that is expressed in any of the art work they’ve drawn so far.

Side post: Natural History Museum #TeamBlueWhales

Attached you will see an affirmation of my transgenderism that I found in the Ocean Life meditation walk we did at the museum and also a picture of my sketches that we did for our visual thinking activity.

Thoughts on this week’s posts 3-31-19

Gene- 3-31-19, comments on posts for this week

First, a shout out to Lamar, who has had a rough week. Your text, Lamar, makes me think of my own engagement with students in Newark – many stories of domestic violence, absent fathers, hunger, lovelessness. One of the conundrums with these stories is trying to navigate the macro-meso-micro conditions that mediate these stories. We can blame 400 years of racism and brutality against people of color in this country (macro) and yet none of that seems a sufficient explanation for the absence of love (meso) that haunts many families and the damage that this absence inflicts on our students (micro). All these levels of damage, of course, are relative and constantly intertwining. How do we confront them as teachers and researchers? How do we begin/join a process of healing that is needed on all these many levels of activity?

I wonder if it would make sense, Lamar, for you to make a quilt of sorts from the drawings, and maybe also a quilt of the selected texts with certain lines and words emphasized. Earlier you wrote about the colliding dreams of your students floating on water, which is an amazing image and idea, and though the ephemeral can be very powerful (see, for example, the work of Andy Goldsworthy), there are also other less emphemeral ways to present collective images/voices of hope and dreams. You could take all the different handwritings of the word “love” or “guns” and join them together in a poster with or without the drawings (and then show them to the students). I’m just quickly spouting out ideas; of course you want to do want makes sense to you. Or you might think about your students doing it. I think both are legitimate.

The line, “Being mean to each other like black and white” stuck out to me because of its non-judgmental voice. My students in Staten Island often say, “why can’t we all just get along?” as if their privilege has no relationship to macro-meso forces. Even young students have absorbed this (hegemonic) way of thinking and it definitely has an appeal to it because it makes it easier to believe that it’s just a matter of faith in individual good will. This optimism and belief in personal-power to create change is also a necessary ingredient of systemic change, but it diminishes the reality of designed and purposeful oppression. Notice that the use of the word “designed” implies that oppression aligned with a vision- something visual. That’s why Mirzeoeff proposes a “countervisuality,” a new vision that we can see and thus design. I wonder if it helps to think of your stduents’ drawings in terms of the creation of a new vision.

I wonder what role the prompts play in the drawings/text.

The line “To live and stay with my family” also struck me. I’m curious about the “live” and the “stay.”

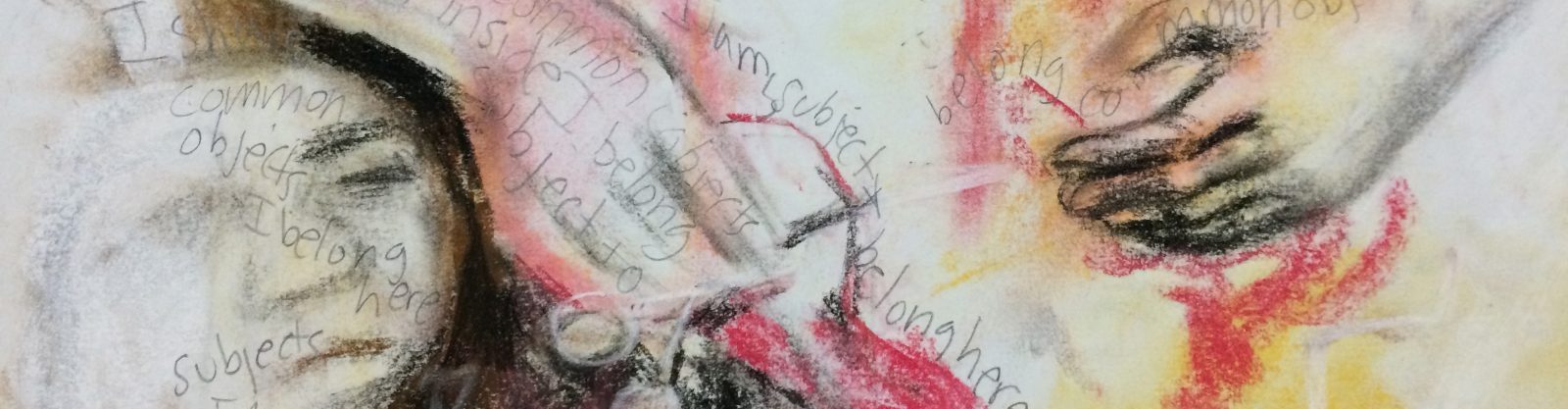

It’s interesting to look at Dahlia’s project after looking at Lamar’s. Dahlia has embraced the role of the artist who can “cook” the work of her students, something Lamar is hesitant about doing. Cooking may not be the right metaphor here, because Dahlia is not mushing things together but carefully and respectfully highlighting, making choices, curating in a way that many of you seem hesitant to do. The two images she constructed are phenomenal; they are visually captivating, evocative and complex. They visually present the “400-year long event” that Christina Sharpe writes about the past of slavery still present in the space and time of her students, her white students as well. And so there is hope in that. Are you going to show these images to the students you quote?

I am also excited to see the poem that Dahlia has extracted from the transcript, an arts-based approach to research that is being used by other researchers as well (see, for example, an article “The Teacher almost made me cry” by Honkasilta et al. that takes lines from different narratives of children with ADHD and turns them into poems). I love the part, “because I know every nook and cranny of Patrick Henry, not just because of the building …because of the people there. But still I have a connection towards the actual building” and think it could be presented in a visually striking way if you wanted to think about doing so. Poems, of course, are visual (think again about Pink’s discussion of how every experience is presented simultaneously in multiple modes even though we can’t talk about experience that way) and I think playing with the words in this poem and their organization could be exciting. Have you ever looked at the way ee cummings writes his poems? You can think about spacing between words and letters, capitalizing, and of course adding actual drawings/photos and marks.

I think you’ve made exciting strides in your work Dahlia!!

The link that Dahlia shared with us under her heading “Incredible art to share” is truly incredible. You should all look at it.

I couldn’t help thinking about the fact that Patrick Henry owned almost 70 slaves despite his oratory against slavery

Since I have made a number of comments about curation, it is interesting to consider how Greg is curating his photos. He is using a contingent-dynamic process; he began by choosing participants but then the participants chose other participants. Greg loses a bit of control here, but in alignment with ideas of participatory research gives curatorial power to others. The photographs themselves are terrific, but to my eye they seem very different from the first set he showed us though like the fist set they are very clean and polished. I get confused, Greg, by your concern with “sample-size” since that is a term usually used when talking about quantitative data that is meant to be generalizable. As far as I know, you are not making any generalizable claims. Where both Dahlia’s project and Lamar’s combine image with text, these photos, thus far, are without captions or participant reflections and comments. As with Lamar’s work, I wonder how the prompt mediates the response and how the prompt even gets interpreted by the participants.

I’ve been listening to Saadiq for the last ten minutes, one cut leading to another. Love that Girl made me think of Marvin Gaye and the Attica Days when we used to dance the “Bump.” A great deal of joy, and yet while that joy is, as Dahlia pointed out last week, necessary to any revolution we want to be a part of, it is not by itself sufficient to dismantle the macro oppressions our communities confront. Mindfulness has been terribly coopted, and yet on the micro scale mindful activities – if practiced in the spirit that Christina Trowbridge presents – has potential power to change macro systems. I find Noor’s comments on Lamar’s hard week and his students’ drawings resonating with me. Lamar is doing care work with his students, but the gap is wide between his students’ healing and their empowerment to transform their worlds so that the care work for their own children will not be necessary. But we have to start where we are. Still, I wonder, Lamar (and everyone else) how you push the tension between catharsis and transformation, and what is the researcher’s role in this process.

It is exciting to think about drawing as “a form of praxis”.

I am increasingly excited about the prospect of all of you exhibiting your work since it is so rich, though you don’t need to make any decisions yet. We can use Noor’s drawing, which I love, as part of the invitation. I’m not sure what it says that her first marks on the paper depicted wine on table! 🙂 Notice how Noor, drawing with the left hand, created a drawing that has all the vivacity of a child’s drawing – it is funny, has character (great lines) and no worries about absolute rendering.

Luis has been using visual methods as tool of self-care and reflection, but so far they have mostly been cries for help because the students are still struggling mightily with calculus. The drawings are not helping them become better at calculus, and even if the drawings helped student to temporarily disengage from solving math problems and find humor in their angst, their desperation will return with the next assessment. On a much more meso scale, the drawing cannot solve the students’ calculus problems any more than the drawings of Lamar’s students will vanquish the dysfunctionality that surrounds them. Can Luis use drawings in a way that will help his students contemplate calculus (visualize calculus?) in way that will both bring peace and breakthroughs? Can it, in other words, be used as a contemplative and healing method to learn math? Whereas Dahlia, Greg, and I think Noor as well are seeking to evoke conditions, situations and experiences, Lamar, Luis and probably Aderinsola are trying to find the bridge between evocation and transformation within their particular focus.

Rainy Sunday Left Hand Drawing

It is a rainy Sunday morning and I chose to try out drawing with the non-dominant hand mindfulness activity from the Townsend piece. It was my first instinct upon reading as I was also asking myself, “when was the last time I drew with my left hand?” The activity proved to be calming and also very amusing as I tried to recreate our class. As you can see my memory is less on the specific but more the overall situation. The table and the wine bottle were the first on the page. While drawing, I was wondering if our fluid experiences in the class (sharing space) can act as a sort of diorama? I was also thinking about Lamar’s post throughout, (I am sending prayers out to you and your students and their families) which also connects to the part of the piece were she writes how teachers are seeking “refuge from the realities of the public schools”. It is powerful that so many folks were trained on mindfulness but I also wonder when funds and policies will go to support communities and families to improve the quality of life for targeted populations? It reflects a real tension I have with mindfulness as a band-aid and in some ways making stress an individual issue versus something that is structurally imposed historically for specific populations. I also know how important it is to build up our toolkit of practices to individually process and heal. I am curious about the power of carving out spaces of refuge for people facing intersectional oppressions – where refuge is denied systematically and what are our next steps in our roles working with diverse populations along various levels of power? I wonder about the feeling of freedom dreams and what they can teach us about the importance of an imaginary refuge in the process towards liberatory actions that meet the realities faced by targeted populations. Given that some public schools are differently and similarly violent, to all the people who inhabit them and particularly burdensome on the youngest and most vulnerable, how might we draw upon art based practices to make shifts on a structural and individual level?

This piece also offered a way for me to think about the different levels of decision making necessary for building a space of learning with diverse perspectives and experiences. She offers the following capabilities;; 1) focusing attention on what is happening in the classroom 2) questioning what is happening in their own emotions 3) teaching objectives reflect students’ needs, 4)questioning what behaviors teachers choose to achieve their objectives. (180) I see these as all a part of intention setting on an individual level but really a good model for structuring school as a collective staff and student community. What if each person drew out their answers to these questions – taking away the element of power and having each person reflect on what they need to learn in a highly oppressive society/school system?

A few powerful quotes:

“In looking at the diorama, with its focus on phenomena of the natural world, the viewer is looking and thinking, and is in the position of the discoverer, rather than the a passive recipient of knowledge transmitted by others.” How does this shift when moving from the natural world to an unnatural public school structure? In this way, does drawing offer us a form of praxis that is not available just through verbal dialogue?

“objects and words can be generative” – Freire

“mindful learning is the continuous creation of categories, openness, to new information, and an implicit awareness of more than one perspective.” Do drawings also offer color, detail emphasis, ways of seeing of the creator?

“drawing is at the root of everything’ – Van Gogh

“Seeing comes before words” – John Berger. Will freedom dreams and art offer us new words to curve liberatory life/educational experiences?

Then I started listening to music – this came on as I was about to post so I will share:

Reflection on Cristina’s Drawing Attention, by Luis Z

Trowbridge C.A. (2017) Drawing Attention. In: Powietrzyńska M., Tobin K. (eds) Weaving Complementary Knowledge Systems and Mindfulness to Educate a Literate Citizenry for Sustainable and Healthy Lives. Bold Visions in Educational Research. Sense Publishers: Rotterdam.

Cristina’s insightful sketching methodology inspired me to examine my own sketching reflection method I am exploring. I wonder what I can employ as an object for students to see and to contemplate upon. In my current sketching exploration, I encourage students to reflect on their impressions or on their stance towards the experience of learning math, but I provide no particular image for them upon which to reflect. This may be fine, but I wonder if I can aid a further evolution of their process of self-reflection ( into perhaps a deeper contemplation) by offering specific images as objects of contemplation, in the method that Cristina does here.

I wondered if the dioramas of natural history and science, which Cristina uses as objects of sketching and contemplation, had particular resonance because of their related subject matter for science teachers and students, i.e. if the chosen content was salient for the impact of this arts-based methodology because of its relation to this particular audience. But I don’t think so. I think there is something more universal in play here. Would dioramas from scenes related to science or nature have provided a comparable catalyst for reflection and contemplation for a different audience? I think so. I suspect that the form of Cristina’s methodological approach was what mattered most— in her modified protocol of Housen’s Visual Thinking Strategy, she still employed his specific question prompts to direct the practice of focused sketching contemplation, but she then created spaces of silence and of mindful contemplation where participants could also have the time “…to look before verbalizing observations and inferences”(174). The methodology provides affordances for each participant’s unique way of seeing, the “plurality” of interpretations possible as evidenced by what each participant views, as the different mountain lion diorama sketches by each participant illustrated (176). Participant teachers also shared the therapeutic benefits to their health and wellness of this methodology by finding such times of “silence and peace” healthful and, unlike most classroom environments, a space where renewed attention could be given to details, and where they did not feel compelled to impose learning perspectives or content upon students (178). However, I cannot discount the universal connection we have to nature, and that this choice in theme may be integral to this methodology, wherever it is applied. I am motivated to consider this thematic as well but also to consider other potential images to catalyze such contemplation in my field of mathematical content.

In addition, Cristina makes the important distinction between mindfulness and contemplation (173). I now ponder that difference within the goal of my current work of authentic student self-reflection , and I consider whether that is different than contemplation. Merriam-Webster conspicuously qualifies the definition of contemplation as a thoughtful consideration that is practiced “…with attention,” or as the act of “regarding steadily.” This quality of “steadiness” that I sense throughout in Cristina’s field notes reminds me of the frequent discussions I have had with students and exasperated parents, where a frequent culprit identified by both was the apparent inability of students to sustain concentration. Perhaps more than my current exploration of student self-reflection for the purpose of emotional processing and healing, contemplation may be the next step of this process, where a strengthening of the ability to sustain concentration becomes a focus, a focus which is so crucial in any learning.

In practice, Cristina observes that “The drawing is about focusing attention to detail and not about the actual sketch” (174). Ways in which fear of failure can be eliminated by sketching, such as Cristina’s later practice of having participants draw with their non-dominant hand, offers options in later reflection practice. It at least raises consideration for other sketching tools I might employ in my sketching self-reflection explorations, such as a proscription that sketching must be related to this class or to this content. How may I support freedom from judgment for my students, including from their own?