Trowbridge C.A. (2017) Drawing Attention. In: Powietrzyńska M., Tobin K. (eds) Weaving Complementary Knowledge Systems and Mindfulness to Educate a Literate Citizenry for Sustainable and Healthy Lives. Bold Visions in Educational Research. Sense Publishers: Rotterdam.

Cristina’s insightful sketching methodology inspired me to examine my own sketching reflection method I am exploring. I wonder what I can employ as an object for students to see and to contemplate upon. In my current sketching exploration, I encourage students to reflect on their impressions or on their stance towards the experience of learning math, but I provide no particular image for them upon which to reflect. This may be fine, but I wonder if I can aid a further evolution of their process of self-reflection ( into perhaps a deeper contemplation) by offering specific images as objects of contemplation, in the method that Cristina does here.

I wondered if the dioramas of natural history and science, which Cristina uses as objects of sketching and contemplation, had particular resonance because of their related subject matter for science teachers and students, i.e. if the chosen content was salient for the impact of this arts-based methodology because of its relation to this particular audience. But I don’t think so. I think there is something more universal in play here. Would dioramas from scenes related to science or nature have provided a comparable catalyst for reflection and contemplation for a different audience? I think so. I suspect that the form of Cristina’s methodological approach was what mattered most— in her modified protocol of Housen’s Visual Thinking Strategy, she still employed his specific question prompts to direct the practice of focused sketching contemplation, but she then created spaces of silence and of mindful contemplation where participants could also have the time “…to look before verbalizing observations and inferences”(174). The methodology provides affordances for each participant’s unique way of seeing, the “plurality” of interpretations possible as evidenced by what each participant views, as the different mountain lion diorama sketches by each participant illustrated (176). Participant teachers also shared the therapeutic benefits to their health and wellness of this methodology by finding such times of “silence and peace” healthful and, unlike most classroom environments, a space where renewed attention could be given to details, and where they did not feel compelled to impose learning perspectives or content upon students (178). However, I cannot discount the universal connection we have to nature, and that this choice in theme may be integral to this methodology, wherever it is applied. I am motivated to consider this thematic as well but also to consider other potential images to catalyze such contemplation in my field of mathematical content.

In addition, Cristina makes the important distinction between mindfulness and contemplation (173). I now ponder that difference within the goal of my current work of authentic student self-reflection , and I consider whether that is different than contemplation. Merriam-Webster conspicuously qualifies the definition of contemplation as a thoughtful consideration that is practiced “…with attention,” or as the act of “regarding steadily.” This quality of “steadiness” that I sense throughout in Cristina’s field notes reminds me of the frequent discussions I have had with students and exasperated parents, where a frequent culprit identified by both was the apparent inability of students to sustain concentration. Perhaps more than my current exploration of student self-reflection for the purpose of emotional processing and healing, contemplation may be the next step of this process, where a strengthening of the ability to sustain concentration becomes a focus, a focus which is so crucial in any learning.

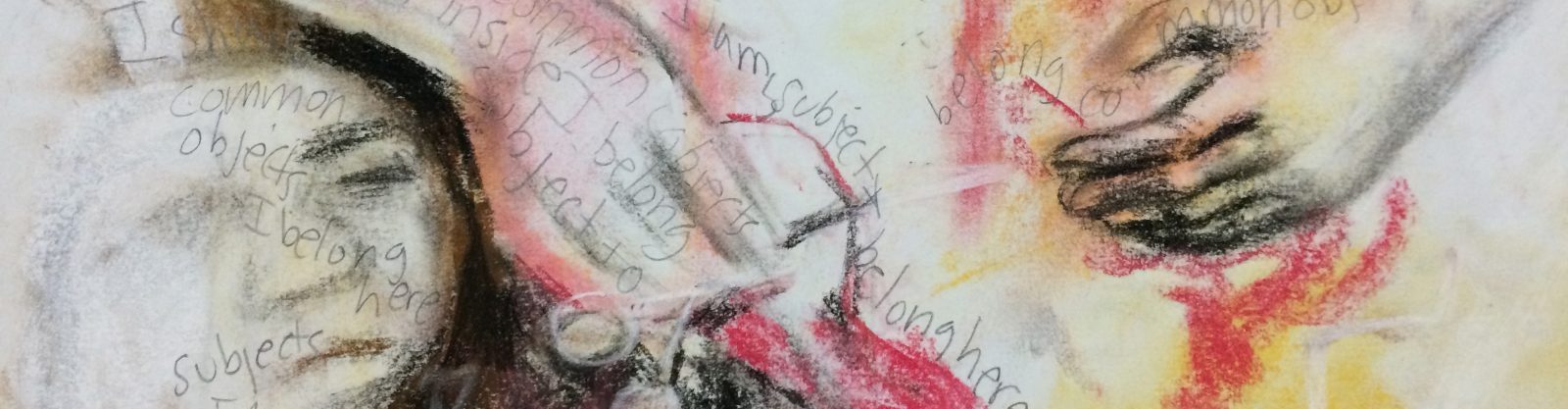

In practice, Cristina observes that “The drawing is about focusing attention to detail and not about the actual sketch” (174). Ways in which fear of failure can be eliminated by sketching, such as Cristina’s later practice of having participants draw with their non-dominant hand, offers options in later reflection practice. It at least raises consideration for other sketching tools I might employ in my sketching self-reflection explorations, such as a proscription that sketching must be related to this class or to this content. How may I support freedom from judgment for my students, including from their own?