Barone, T., & Eisner, E. (2006). Arts-based educational research. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli, & P. B. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complimentary methods in education reserach (pp. 95–110). Washington, D.C.: American Educational Research Association.

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2012). What is and what is not arts-based research. In Arts-based research (pp. 1–12). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Eisner, E. W. (2001). Concerns and aspirations for qualitative research in the new millennium. Qualitative Research, 1(2), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100202

One of the primary challenges that confronts me from this first set of readings is the need to make a distinction between art and arts-based research, that is, the determination of what is uniquely able to be obtained not solely from an encounter with art, but from the practice of arts based research.

With respect to art, Eisner (2001) evinces the ability of visual art to express “…by nuance and drawing attention to particulars, which …slow down perception and invite exploration” (Dewey, as cited in Eisner, 134). Eisner’s focus is to compare the similarities of the quality of art to that of qualitative research. What interested me was his observation that “Researchers involved with human relationships do not solve problems, they cope with situations….whose resolutions lead to other situations” (138). Further, there exists the potential to address the concept of form, for the artist knows “…that form and content cannot be separated” (138). It is vaguely provocative: “..that the form of representation one uses has something to do with the form of understanding one secures” (139). These would certainly be components to be mindful of in the design of art-based research. Though Eisner believes it is necessary to theorize arts-based research, I am not yet convinced by this argument.

Barone & Eisner (2012) reaffirm the role of art, and art-based research in particular, as one means of seeking and expressing truth, a way to provide “methodological permission for people to innovate with the methods they use… “(2), which may not necessarily conform to that of the conventional scientific paradigm. But what are the more general kinds of truth beyond that of scientific propositional truths, and how can such truths be sought and expressed? In Heidegger’s philosophy , Truth is more generally defined as revelation, the experience of unhidden-ness. Perhaps this is one possible notion that I suspect would be relevant in seeking other forms of truth, those less easily quantifiable, and even ineffable.

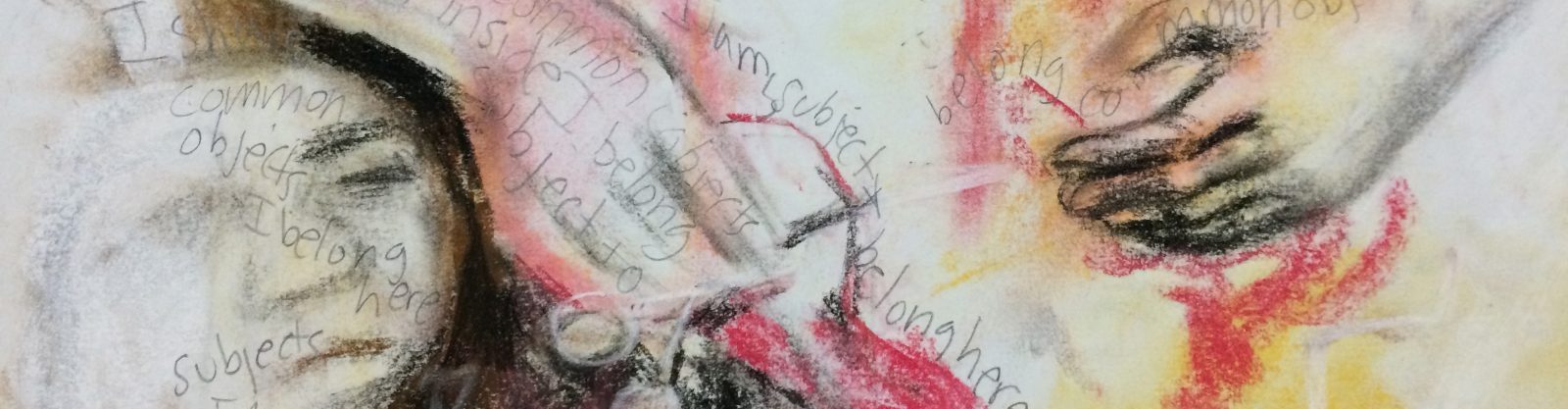

Seeking expression for such non-propositional forms of truth has value, but what value may it have as a research methodology? Barone & Eisner (2012) allude to its potential to “..adumbrate in symbols something important….that can become a source for debate and deliberation” (5), and to function as …”illuminating vehicles” in research activities (6). I think it can allow students a wider canvass upon which to express and un-hide their thinking, both to others, such as the teacher, and to themselves. I also believe in the primacy of developing aesthetic judgment, which ABR may engender in students, and which I believe may most enable students to appropriate knowledge and to exercise power and discrimination over it. As Barone & Eisner (2012) comment, arts-based research is “..the utilization of aesthetic judgment and the application of aesthetic criteria in making judgments about what the character of expected outcomes is to be” (8). (however, I do think that his later generic descriptions fall short of developing this thread, i.e. that ABR’s benefit include the ability “…to create an expressive form that will enable an individual to secure an empathic participation in the lives of others and in the situations studied” (9), or that arts based research is “an emotionally drenched expression that makes it possible to know how others feel.” Not as helpful. I would like to develop myself.. )

Other generalities may not uncover the true value of arts-based research, such as the assertion that it “…addresses complex and often subtle interactions and that it provides an image of those interactions in ways that make them noticeable… It is a “heuristic through which we deepen and make more complex our understanding of some aspects of the world (3)”. I am not so sure that complexity is what is always desired. Specificity and detail, perhaps even simplification, can also be possible, as Eisner (2001) asserts below. Nevertheless, I would like to explore potential methods relevant to me within the ABR methodology: how art can provide emotional dimension to STEM education; how art can be used as a tool for student self-discovery; how the use of limitation can, like in theatre, catalyze the imagination; how art can support equity in the STEM classroom (not only participation, engagement, but as an aid in understanding, and in precision of expression)…. Can art-based research unify content areas that presently appear distinct? Can the precision of the scientific inform traditional art and elevate it?

I appreciate the cautionary in both Rose and Eisner’s articles. What does “critical” mean in the context of ABR? She does state the danger of a criticism that is both “easy and ineffectual, because it changes nothing of what it criticizes “( Rose 29). The act of observing art for the sake of critiquing it can in effect cheapen the very experience it has the potential to evoke (29). (As I mentioned earlier, I am not sure that Art is meant to be theorized.) Further she affirms that “there are many times that I yearn for something in excess of the research” (Holly in Cheetham et al., 2005:88, as cited by Rose,29). Scholars emphasize “the embodied and the experiential as what lies in excess of the representation” (Marks and Hansen, as cited by Rose, 29). Delueze suggests, with reference to cinematic art, that perhaps this “beyond” may consist in the ability to “…lose control of ourselves, undo ourselves, forget ourselves while in front of the cinema screen” (29).

Rose, G. (2016). Visual Methodologies (4th Edition). London: SAGE Publications.

Rose also insinuates some ethical concerns with subjects in ABR. Thus, I would expect research guidance is vitally important and necessary in order to responsibly and ethically employ arts-based research in the classroom, and more generally, in educational research. It is not anyone’s right, for instance, to expose or to reveal the feelings of others, if they are not so informed and freely participating in the search, etc..

In the arts, there is the notion of subjectivity and relativity in judgment, an indeterminacy that can appear to subvert its value in arts-based research. However, Eisner (2001) addresses this and provides a counterpoint to universality: art can in fact delineate distinctive individuality of creation and expression of understanding. Perhaps the most value for pedagogy that an arts-based research method can assess is that distinctiveness “…if the tasks that students are asked to engage in are sufficiently open ended to allow their individuality to be expressed and if the appraisal of their performance employs criteria that suit the work to be assessed”(142). It is not valid to compare one’s work with that of another in this context either. He reminds us of Dewey’s cautionary note about the uniquely distinctive and particular nature of art, and that “…nowhere are comparisons more odious than in the arts” (141). Lastly, work and skill with art must be developed as well as appreciated by practitioners of ABR. “You need refined sensibilities, you need an idea, you need imagination, and you need technical skills” (143).