Luttrell, W. (2010). A camera is a big responsibility: a lens for analysing children’s visual voices. Viusal Studies, 25(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2010.523274

Luttrell, W. (2016). Children framing Childhoods. In J. Moss & B. Pini (Eds.), Visual research methods in educational research (pp. 172–188). Palgrave, Macmillan. Retrieved from http://www.wendyluttrell.org/framing-childhoods/

In “Children framing Childhoods,” Luttrell introduces the concept of “collaborative seeing,” the practice of looking and contextualizing with others what they wish to express as salient in their lives (181):

“Theoretically speaking, collaborative seeing allows us to engage what Weis and Fine (2012) call ‘critical bifocality’, which links individual meaning making to larger discourses, public policies and conditions that ‘come to be woven into community relationships and metabolized by individuals’ “(Weis & Fine 2012, p. 174)(p.181)

This innovative use of photography, and later digital and video methods, in a sociological research methodology enlarges the potential and scope for the co-researcher paradigm, and the opportunity for authenticity for participant emotional self-development and growth. This visual method of childhood photography situates adults more properly as respectful of the full lives of children, lives that are equally worthy of adult attention, curiosity and emulation, a curious converse to the way it is often presumed that children should emulate the lives of adults.

Luttrell reaffirms the importance of an effective design and systematic analysis. I like her careful attention to the use of prompts throughout the course of the longitudinal study. For children participants, the prompt was “You have a cousin moving to Worcester and attending your school. Take pictures that will help him/her know what to expect…, “ and, for the adolescent middle schooler, “Take pictures of what matters to you” (Children, p.175), and so forth as they aged. However, what was most apparent to me is the intensity of analysis that is necessary in order to both effectively engage participants in follow-up interviews and systematically sift through large amounts of data in order to draw appropriate inferences. The latter need for systematicity is reflected by the detailed coding that was part of a comprehensive picture analysis (A camera, 229). Evidently, and even counterintuitively, an arts-based qualitative study analysis, despite one in which control of content is ceded to children too, still requires specificity and comprehensiveness in design and analysis. In fact, I get the distinct impression that qualitative analysis can be more arduous and rigorous than quantitative analysis—more complexity is in play.

I still experience a velleity of the ethical quandaries I have raised earlier from Luttrell’s work as well, but to a lesser degree than I have felt in methods of community arts-based research articles we recently studied. Perhaps it is because the students are the sole creators of the art in her photography method. Yet, she herself acknowledges that the quandary still exists. In her other article, “A camera is a big responsibility,” she states that the “..persistent conundrum in this mode of research is finding the line between children’s voices and those of adult researchers,” a conundrum she concedes she does not resolve but at least wishes to acknowledge. In “Children’s Voices,” she indeed took great care to involve participants (children) in the research authentically and transparently. I do feel that children were afforded the respect and the space to exercise independent volition and control over the form and nature of their participation. In fact, the research here allowed students a means for meaningful self-reflection and growth, including that of examining the central aspect of the influence of family and the wider community on the formation and negotiation of childhood identity. Any understanding gleaned by researchers is thus not initiated from an imposition, but rather by a researcher’s intention to…”…listen carefully and systematically” (Camera, 226).

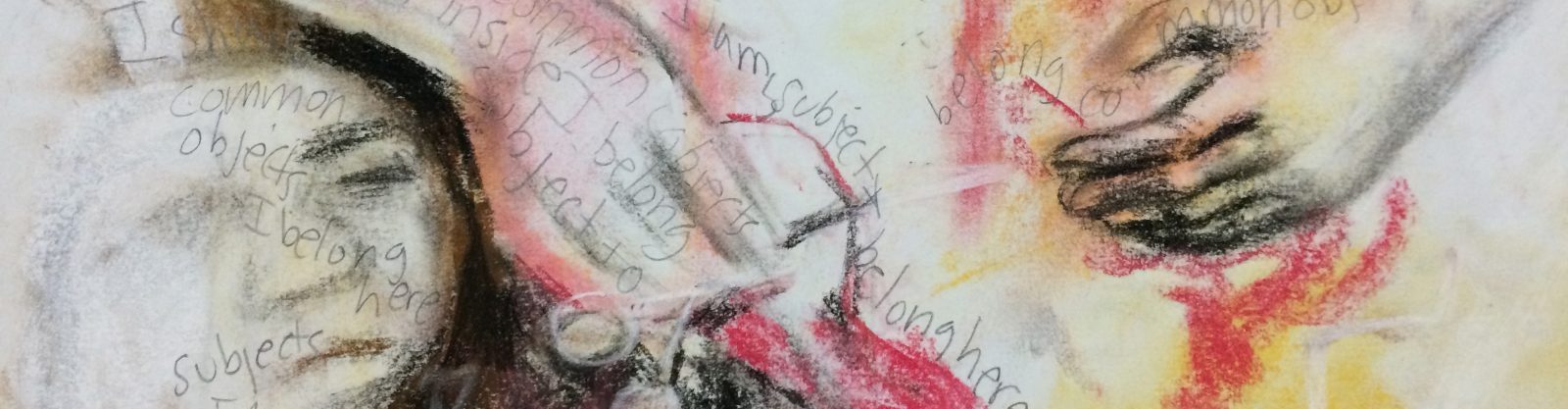

Luttrell expands on child-centered methodologies in “A camera is a big responsibility,” where a closer look at the theoretical framework undergirding the concept of voice is examined, and where the method offers a means to unlock the “hidden transcripts of power expressed in children’s photography” that often can be unduly influenced by dominant ways of seeing (225). She makes the entwinement of photography and narrative salient, in that the lack of linearity and logic endemic to both can be the very form and value that is characteristic of this type of research. This observation encourages me to persist in my visual qualitative work, despite doubts about the “unscientific” and “free form” expression afforded to and generated by students in my visual self-reflection investigation.

Students’ work in “A Camera..” also serves, perhaps more importantly, as a catalyst to potentially more comprehensive exploration and dialogue afterward. For instance, Luttrell engenders a multiplicity of perspectives in a student’s voice through multiple “audiencings” of the work they produced (227). Through this design, she gleans the salience of the “work of care” as a primary expression across students’ work. I also wonder what might be the other salient themes observed, the others that she insinuates were “beyond the scope of the article” (230).

“While ‘voice’ should not be conflated with language, language does allow for some expression of ‘voice’ that is beyond words” (A Camera, 233). And the camera can be one visual method that “affords voice” to those who otherwise may not have one in “the body politic”(233), and one method I hope of many others that can transform the often unexamined asymmetric relation between researcher and subject into one of parity between adults and children as co-researchers.