Pink, S. (2011). Multimodality, multisensoriality and ethnographic knowing: social semiotics and phenomenology of perception. Qualitative Research, 11(3), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111399835

Jordan, C. M. (2017). Directing energy: Gordon Matta-Clark’s pursuit of social sculpture. In Gordon Matta-Clark: Anarchitect (pp. 36–63). New Haven, CT: The Bronx Museum of the Arts and Yale University Press.

In PInk: “Perception begins in the body and ends in objects”(Csordas, 1990, p. 8, as cited in Geurts, 2003)” (265).

Theme: The visual in use as a sensory ethnographic evocation in “phenomenological” ethnography, rather than as a traditional recording of data in classical ethnography, can lead to a more comprehensive anthropological ethnography. Pink reaffirms Merleau-Ponty’s views that the body senses with all its organs simultaneously and in an interconnected manner. But in the attempt to linguistically express that sensory experience we find restriction by the conventional five-sensory model. The breadth of sensory experience, requiring a true “phenomenological ethnography,” cannot, even in moments, fit neatly into the limitations of linguistic-based models. (270)

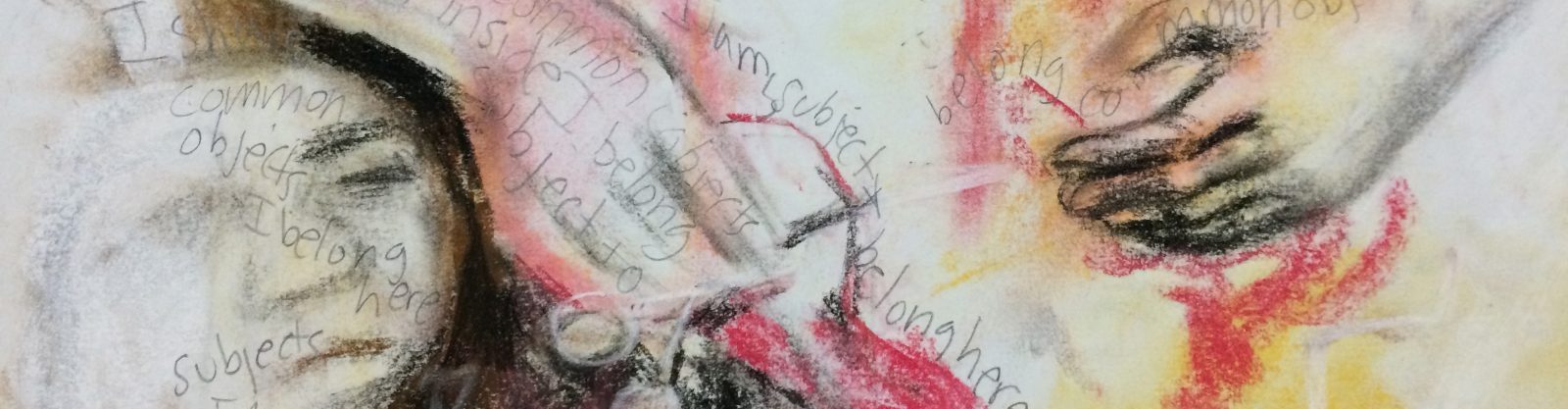

Not only can Art be used as a tool of expression when the linguistic mode may not be sufficient to the task, a phenomenological ethnography of ”being with” seeks to understand and express what others understand and feel. The visual, for instance, is not viewed merely as a “photographic” recording of data or evidence as in classical ethnography, but as a means to elicit, empathize, or to evoke a more comprehensive experience of a moment, a true anthropological ethnography. Imaginative use of even one sensory mode, such as the visual, say, can evoke a multi-sensory experience (synaesthesia). It is intriguing that the visual alone can be more precise than the linguistic: although Pink disagrees with Kress’s binary schematic between words and images in general, she appears to agree with Kress’s (2005) counterintuitive assertion that images can depict experience with greater fullness of meaning, detail and precision, while words are more “general, ….empty and vague.” (264). Although most would agree that words, by context for instance, are indeed imbued with meaning anew in any instance by the hearer/reader (264), is the visual truly less amenable to that distortion in communication? It is so counterintuitive that it must be true.

I am most intrigued by the use of visual arts as a means of approaching a fuller anthropological ethnography, with its attendant precision, and how this ethnography would manifest in a range of practices, including that of educator, student and researcher.

——————————————————————————————————————

So, is Matta-Clark a community activist who employs arts-based research, or an artist who employs community-based research? Although either description is easily justified, the former may be closer to the core of his identity. Ultimately, he wanted to realize community engagement and empowerment, the identification of and resistance to socioeconomic inequality and governmental neglect, and a heightened community political awareness. Matta-Clark’s experience may be emblematic of realizing the potential of this methodology in other vocations that aim to employ arts-based research, including educators who aim to employ arts-based research. It also highlights possible questions of ownership and ethics.

His arts-based research provides a tool for participants to shape their world. Ironically, this was most apparent to me in the photo of the four men sitting in a dirt lot with shovels in hand, ready to begin that act of creation upon a blighted, desolate lot. The shape that it would take was yet to be realized. I wonder what it was going to become. Completed installations, including Pig Roast and restaurants such as Food, Matta-Clark incorporated highly participatory experiences with food in community. He aimed to employ “professional and non-professionals” alike as participants in work valuing inherent “human capital,” not the narrow political or economic capital that is often absent from such communities. The work characterized the creation of a community that together invests in themselves and addresses together the problems that they face.

Is the question about the attribution and ownership of community-based works of art in fact an important question or not? There is an ethical rub here that Jordan insinuates. Ownership of many of these works and extant installations were, in the end, attributed solely to the artist, as was the case with Matt-Clark and Beuys, although many community residents together created the work. Is this important? If it was their aim, then these great artists were ultimately not successful in that attempt to “…eliminate the hierarchic relationships between [artists] and their audiences”( 53).

The question of durability is related. After the death of Matta-Clark, and of Beuys, the power of their work would dramatically diminish later for those who were not present firsthand to experience it with the artists’ direction (53). Evidently, the artist was the lodestar of an ephemeral artefact of community shaping only for an instant in time. Perhaps the the return of attribution to the progenitor artist also made vulnerable the legacy of that art’s influence. Nevertheless, the arts-based research in shaping community did in fact impact the community in that time in significant ways. The fact that such artefacts are not eternal, like great art is supposed to be, does not diminish the fact of what the community created, even if ephemeral, using arts-based research. Thus, the question, “Was it ever art?” is moot. So is the question “Whose art was it?” The only answer that matters is that the sensibility of art as a methodology was successful in allowing citizens to create and shape a community, at that instant in time. It is also crucial that the research project was conducted ethically, with transparency and respect for all who participated. I like that art is not held in reverence here; the community is. We do not have to esteem “art” too highly in arts-based research, where we have the right to demote art to take a subordinate role in the service of other higher purposes, even other higher purposes that are ephemeral.