Gene- 3-31-19, comments on posts for this week

First, a shout out to Lamar, who has had a rough week. Your text, Lamar, makes me think of my own engagement with students in Newark – many stories of domestic violence, absent fathers, hunger, lovelessness. One of the conundrums with these stories is trying to navigate the macro-meso-micro conditions that mediate these stories. We can blame 400 years of racism and brutality against people of color in this country (macro) and yet none of that seems a sufficient explanation for the absence of love (meso) that haunts many families and the damage that this absence inflicts on our students (micro). All these levels of damage, of course, are relative and constantly intertwining. How do we confront them as teachers and researchers? How do we begin/join a process of healing that is needed on all these many levels of activity?

I wonder if it would make sense, Lamar, for you to make a quilt of sorts from the drawings, and maybe also a quilt of the selected texts with certain lines and words emphasized. Earlier you wrote about the colliding dreams of your students floating on water, which is an amazing image and idea, and though the ephemeral can be very powerful (see, for example, the work of Andy Goldsworthy), there are also other less emphemeral ways to present collective images/voices of hope and dreams. You could take all the different handwritings of the word “love” or “guns” and join them together in a poster with or without the drawings (and then show them to the students). I’m just quickly spouting out ideas; of course you want to do want makes sense to you. Or you might think about your students doing it. I think both are legitimate.

The line, “Being mean to each other like black and white” stuck out to me because of its non-judgmental voice. My students in Staten Island often say, “why can’t we all just get along?” as if their privilege has no relationship to macro-meso forces. Even young students have absorbed this (hegemonic) way of thinking and it definitely has an appeal to it because it makes it easier to believe that it’s just a matter of faith in individual good will. This optimism and belief in personal-power to create change is also a necessary ingredient of systemic change, but it diminishes the reality of designed and purposeful oppression. Notice that the use of the word “designed” implies that oppression aligned with a vision- something visual. That’s why Mirzeoeff proposes a “countervisuality,” a new vision that we can see and thus design. I wonder if it helps to think of your stduents’ drawings in terms of the creation of a new vision.

I wonder what role the prompts play in the drawings/text.

The line “To live and stay with my family” also struck me. I’m curious about the “live” and the “stay.”

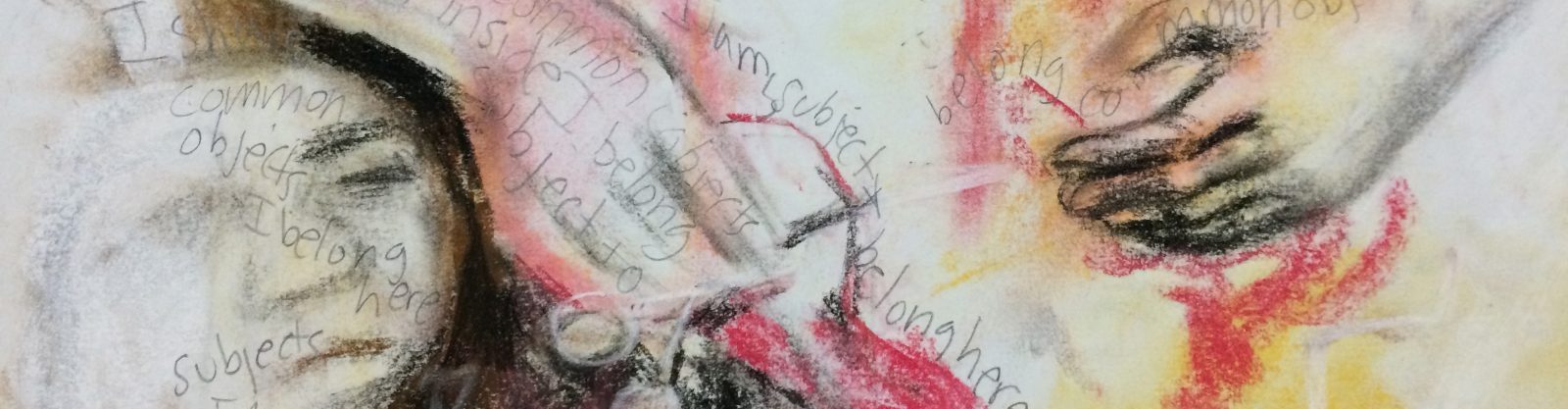

It’s interesting to look at Dahlia’s project after looking at Lamar’s. Dahlia has embraced the role of the artist who can “cook” the work of her students, something Lamar is hesitant about doing. Cooking may not be the right metaphor here, because Dahlia is not mushing things together but carefully and respectfully highlighting, making choices, curating in a way that many of you seem hesitant to do. The two images she constructed are phenomenal; they are visually captivating, evocative and complex. They visually present the “400-year long event” that Christina Sharpe writes about the past of slavery still present in the space and time of her students, her white students as well. And so there is hope in that. Are you going to show these images to the students you quote?

I am also excited to see the poem that Dahlia has extracted from the transcript, an arts-based approach to research that is being used by other researchers as well (see, for example, an article “The Teacher almost made me cry” by Honkasilta et al. that takes lines from different narratives of children with ADHD and turns them into poems). I love the part, “because I know every nook and cranny of Patrick Henry, not just because of the building …because of the people there. But still I have a connection towards the actual building” and think it could be presented in a visually striking way if you wanted to think about doing so. Poems, of course, are visual (think again about Pink’s discussion of how every experience is presented simultaneously in multiple modes even though we can’t talk about experience that way) and I think playing with the words in this poem and their organization could be exciting. Have you ever looked at the way ee cummings writes his poems? You can think about spacing between words and letters, capitalizing, and of course adding actual drawings/photos and marks.

I think you’ve made exciting strides in your work Dahlia!!

The link that Dahlia shared with us under her heading “Incredible art to share” is truly incredible. You should all look at it.

I couldn’t help thinking about the fact that Patrick Henry owned almost 70 slaves despite his oratory against slavery

Since I have made a number of comments about curation, it is interesting to consider how Greg is curating his photos. He is using a contingent-dynamic process; he began by choosing participants but then the participants chose other participants. Greg loses a bit of control here, but in alignment with ideas of participatory research gives curatorial power to others. The photographs themselves are terrific, but to my eye they seem very different from the first set he showed us though like the fist set they are very clean and polished. I get confused, Greg, by your concern with “sample-size” since that is a term usually used when talking about quantitative data that is meant to be generalizable. As far as I know, you are not making any generalizable claims. Where both Dahlia’s project and Lamar’s combine image with text, these photos, thus far, are without captions or participant reflections and comments. As with Lamar’s work, I wonder how the prompt mediates the response and how the prompt even gets interpreted by the participants.

I’ve been listening to Saadiq for the last ten minutes, one cut leading to another. Love that Girl made me think of Marvin Gaye and the Attica Days when we used to dance the “Bump.” A great deal of joy, and yet while that joy is, as Dahlia pointed out last week, necessary to any revolution we want to be a part of, it is not by itself sufficient to dismantle the macro oppressions our communities confront. Mindfulness has been terribly coopted, and yet on the micro scale mindful activities – if practiced in the spirit that Christina Trowbridge presents – has potential power to change macro systems. I find Noor’s comments on Lamar’s hard week and his students’ drawings resonating with me. Lamar is doing care work with his students, but the gap is wide between his students’ healing and their empowerment to transform their worlds so that the care work for their own children will not be necessary. But we have to start where we are. Still, I wonder, Lamar (and everyone else) how you push the tension between catharsis and transformation, and what is the researcher’s role in this process.

It is exciting to think about drawing as “a form of praxis”.

I am increasingly excited about the prospect of all of you exhibiting your work since it is so rich, though you don’t need to make any decisions yet. We can use Noor’s drawing, which I love, as part of the invitation. I’m not sure what it says that her first marks on the paper depicted wine on table! 🙂 Notice how Noor, drawing with the left hand, created a drawing that has all the vivacity of a child’s drawing – it is funny, has character (great lines) and no worries about absolute rendering.

Luis has been using visual methods as tool of self-care and reflection, but so far they have mostly been cries for help because the students are still struggling mightily with calculus. The drawings are not helping them become better at calculus, and even if the drawings helped student to temporarily disengage from solving math problems and find humor in their angst, their desperation will return with the next assessment. On a much more meso scale, the drawing cannot solve the students’ calculus problems any more than the drawings of Lamar’s students will vanquish the dysfunctionality that surrounds them. Can Luis use drawings in a way that will help his students contemplate calculus (visualize calculus?) in way that will both bring peace and breakthroughs? Can it, in other words, be used as a contemplative and healing method to learn math? Whereas Dahlia, Greg, and I think Noor as well are seeking to evoke conditions, situations and experiences, Lamar, Luis and probably Aderinsola are trying to find the bridge between evocation and transformation within their particular focus.