Restler, V. (2017). Re-visualizing Care: Teachers’ Invisible Labor in Neoliberal Times (the digital assemblage)

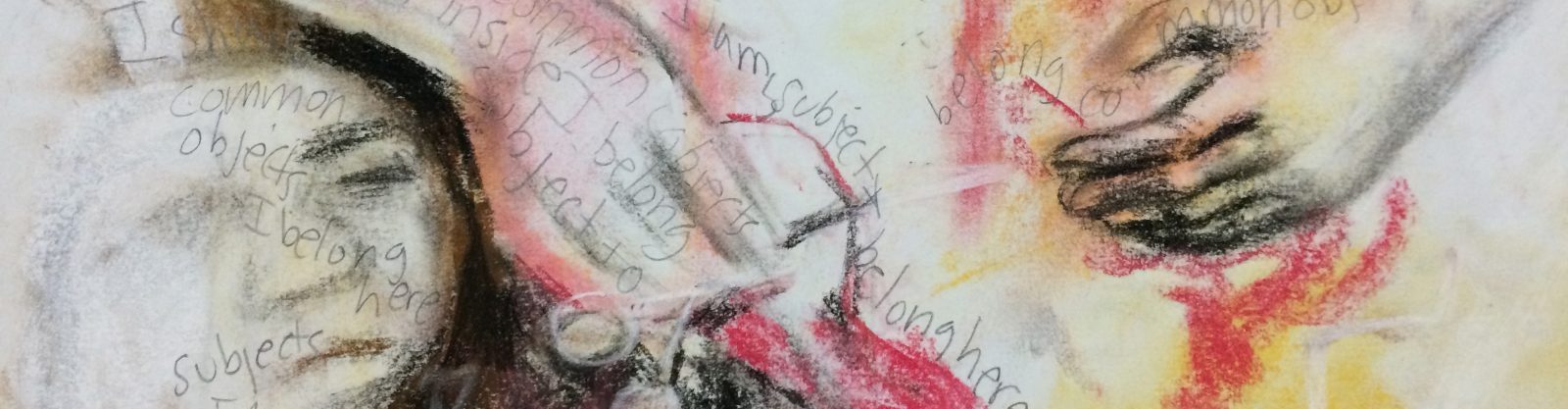

Although I understand this digital assemblage may be only a portion of the dissertation research, the work appears to push the parameters of the practice of collage to a scope more generally encompassing that of evocative ethnography. The content of the images of artefacts produced by rubbings are dictated by what exists contiguously in the space, and return the viewer to a “haptic seeing” of that space. While the juxtapositions may in fact appear to be disjointed at times, like collage, they may also appear complementary and whole.

The insightful way that the author exploits her role as “artist” allowed her to position herself as an adjunct to the other participants of her research, rather than as an outside observer, in order to subvert the perceived “criticality” of the gaze upon teachers by a “researcher.” It seems to effectively minimize the natural barriers that those observed erect against “outsiders” whose presence is often judgmental. “Claiming ‘artist,’ was a form of release, an acceptable excuse for my odd objectives” (Restler, positionality/art, p.1).

The final dyad, care/tactile epistemology, does serve to express the care demonstrated both by the researcher in the tactile sensitivity in creating representations of the life in a classroom, and by the teacher in the myriad details of preparing a clean, inclusive environment for students. However, the connection of this methodology to new and expanded epistemologies is not clear to me.

What is beyond doubt is the impossibility to capture any comprehensive image of a reality, even of any infinitesimal moment. She states in reference to the particularity and the locality of the rubbings that, “…they remind us of all that can’t be seen and known about the ever-changing, relational, and ephemeral pedagogical moment” ( Restler, Beyond Rubbings, conclusion). We are finite in capability, thus necessarily incapable of attending to the infinity of infinitudes present in each moment that passes. The dissertation encapsulates this humility, not only in the practical limitations of being able to rub only a selected number of items, or of rubbing 3 dimensional figures into 2-dimensional representations, but also in the fact that any means of showing aspects of care can only be partial, of only one perspective of a moment that has passed, and thus an incomplete visual testament of the true breadth and depth of teachers’ work.

Perspectives or aspects of teacher care evoked by the work will be not only be different for each viewer, but perhaps even ultimately ineffable. Like a visually tactile Scheffer stroke, Restler’s descriptions of the work thus also makes evident to me the inadequacy of trying to articulate its precise objectives for practice or pedagogy through the use of language, which is itself inadequate to the task. Despite the specificity of the work, “These images don’t aim or claim to measure,” (Restler, Beyond Rubbings, conclusion). Though it may be difficult to put into words exactly what the images do aim or claim to express, it does evoke a means to honor the work of teachers, although I believe it to be a testament that would be valid for both neoliberal or classical liberal times.

Some questions that came to mind…

Was there practical limitations for scheduling the visit on the last day of school? About getting student participation (although it may not be a central objective of this research focused on teachers).

How did you get permission to enter the school for this work?

What is the platform host site of this work? Is scalar the blog publisher? How did you choose the format and resources to publish your work?