Both Luis and Lamar discuss modes through which experiences are conveyed and the limits of language to express the fullness of those experiences, what Luis calls the “mix of lived experience.” I think one of Pink’s main contributions to the discussion is her insight that no mode by itself (including the visual mode) is itself sufficient to the task of carrying experience, and yet each mode evokes a sensory response that invokes the other modes because on the level of the body experience is not allocated to only one sense but engages them all. When we talk about experience, because of the “crisis of representation,” we don’t have the language to do it justice. If we did, then we wouldn’t be talking about modes at all.

Of course the sensing of an image is mediated by how the viewer (hearer, reader) has learned to engage with her world, and Lamar points out (as Pink does) that these ways of engaging are culturally mediated. For Lamar to think with his students about the different ways to sense Freedom is a brilliant idea. in addition to the 5 senses, we might probe motion, balance, ethics, and intuition as sensory ways of enriching how we think of our own experiences. And there are certainly other “senses” as well.

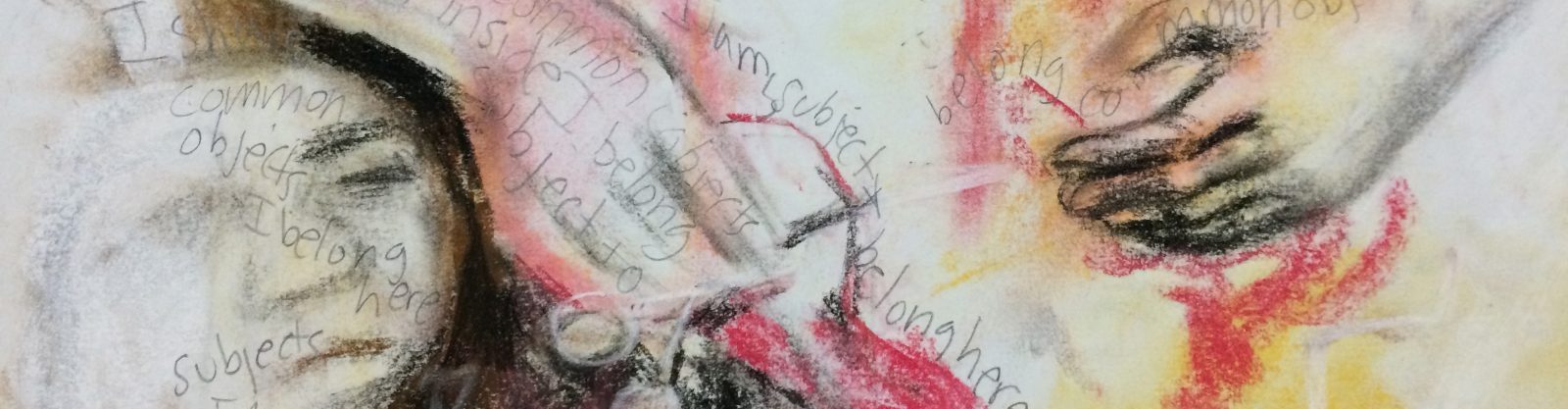

I wonder if what Luis is calling “distortion” is what happens when artifacts/art are interpreted by the viewer, because the viewer (hearer, etc) immediately senses through experiential ways of feeling and interpreting that are not identical to those of the “creator.” By “distorting,” the audience to the art/artifact is becoming a creator as well, though when the artist’s goal is very specific that may not be to her liking (but it’s also not within her control). When we are using art to express what “others understand and feel” the discussion obviously becomes more complicated given the impossibility of conveying what we ourselves feel.

When we think about poetry, we think about words, music, rhythm and imagery. This is text as art and multisensory. Has it been used for revolutionary purposes? We could argue that it has been used to at least inspire, something we might say about visual art as well.

Luis asks if Matta-Clark is more of an artist or an activist, and both Luis and Lamar applaud his engagement of the community during his art-based endeavors. Just as we expand the definition of research to include any means through which we explore, we could expand the concept of art to include anything that incites new expereinces, that breaks established boundaries, that breaches established ways of thinking. Maybe we could describe anything that anyone makes as art. Noor, in her previous post, writes about visual arts-based research as a “form of humanization.” Could we think of any research process that puts us in touch with our full human potential as art? Does this blurring of boundaries serve us (as individuals and as societies) or does it muddy the waters in ways that are not helpful to our goals? Do you think Theaster Gates was more successful than Matta-Clark in involving the community in the process of creation, in help the everyday person realize their artistic self?

Luis writes about ethics and ownership in relationship to the Matta-Clark article and how important it was. These are good questions to ask. I was wondering how to read the photo of the homeless person on page 42. The photo was attributed to Matta Clark and exhibited in an important Manhattan gallery. Do you think it was exploitative? And how does it make us think about photographic ethics