2/3/19

Hello all:

I thought I would take this time to reflect on the comments that have been posted on our website. I’ve really enjoyed reading them and thinking about them, and I look forward to us continuing the discussion tomorrow.

It seems to be that all who posted responded strongly and mostly favorably to the Barone and Eisner piece, with Luis being a bit skeptical, an attribute of his that will help us all to make sense of what we’re doing. It is interesting to me that when Lamar cited from Wang, he cited Wang’s excerpts from Eisner. This makes total sense, because Eisner, who is really seen as the central founder of arts-based research as an academic “discipline,” looks at arts-based research through a very broad and exhilarating lens. Creativity, disruption, imagination, ambivalence, understanding evocation and exploration are all celebrated by Eisner and Barone; their writing is best in my opinion when they don’t try to define precisely what arts-based research is but concentrate on what it can do. I laughed when Dalia wrote that despite her impulses that seem difficult to constrain, she found Wang’s organized and logical categorizations useful (as did Gregory), and of course Rose is even more analytical and “scholarly”. I, too, find Wang et al., useful for thinking about arts-based approaches to research, but I remain unsatisfied with Wang et al’s definitions (I think the categories are very permeable and their borders unsustainable). Meanwhile Rose presents the many different aspects of any artwork/artifact that mediate how it works and is seen and felt, but as Lamar points out it is unclear to what degree the researcher should try to predetermine the evocative success of any work to others given the impossibility of prediction and the possible negative affect that over-thinking might have on the creative process. Luis goes even further, questioning if art should be theorized at all. After all these exhilarating ideas that Barone and Eisner propose as strengths of arts-based research are all a bit fuzzy, hard to pin down and very subjective. And yet Luis, citing Heidegger, talks about the experience “of unhidden-nees.” In doing so he addresses Lamar’s question, paraphrased here, “Can art help my students discover what they are unaware of. Can drawing help them contemplate their own sense of what freedom means? If so, isn’t that enough?

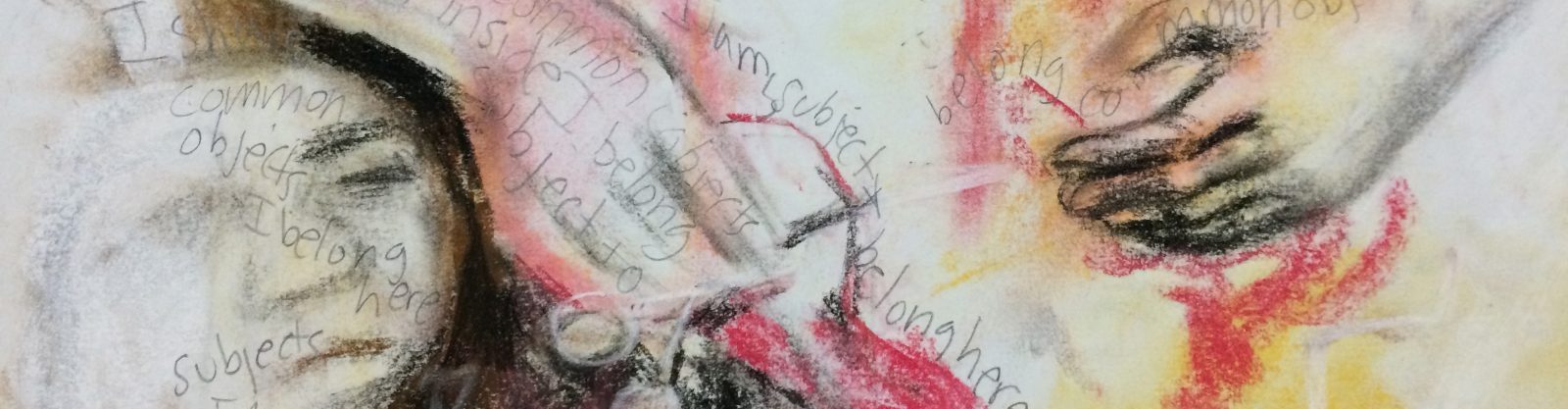

I think it’s interesting that for Gregory, the categorizations by Wang et al helped him see the artifacts/art produced by Victoria as legitimate self-standing research not merely appendages (or illustrations) to written text. The constraints of categories made it possible to abandon the constraints. If the work on its own gives you insight that written text does not provide, insight that is “beyond” words, then does it count as research? What do we value qualitative research anyhow?

Dahlia ponders how the form we choose contributes to the constraining and shaping of meaning (and of course the affordance and illumination of meanings as well). We want to acknowledge the importance of that insight and consider it when embarking on our own research; I believe Luis makes this point as well. At the same time we want to be humble about our goals, understanding that our purpose is explore not necessarily to find. It is what makes arts-based research so exciting or, as Dahlia emphasizes, we use arts-based methods heuristically to gain a deeper and more complex “understanding of the world.” Luis, if I understand his text correctly, is more interested in art as a practical teaching method. And indeed there are studies of schools that correlate arts infusion with academic achievement, in part I think because of the emotional effervescence that circulates through a school in which creativity and imagination are valued. I’m still thinking about what Luis means by precision in expression, something we will no doubt discuss further. In arts-based “products,” precision might be equated with emotional resonance, but Luis is being more down-to-earth than that.

Lamar, clearly an advocate for his students, deliberates whether the drawings his students make are viable and significant because of what they do for their makers regardless of what others might think. I wonder if the students who make those drawings are using the drawing process heuristically (Dahlia liked that idea), trying to figure out how they feel about freedom through the drawings they make. Are the drawings helping them think about freedom. If so, we could call this “art as research”- using Wang et al.’s term: they are using art to be reflexive, to makes sense of their world. If this is taking place, no other justification for the process is needed. And yet, how do we know that the students are using the drawings that way rather than as maybe doing something simpler (though also legitimate)– quickly deciding what freedom looks like and then documenting that image. If my memory serves me well, the images you showed us Lamar (certainly one of them) were of a nature scenes (I remember flowers and pretty colors). We often, idyllically, associate nature with peace and freedom, and that might be a very surface metaphor for freedom. There is a body of literature (I’m thinking specifically of Lefebvre’s The production of space) that argues that we maintain pockets of nature (parks, national forests) as a symbol of freedom, which allows us to destroy nature writ large. So I am curious if the drawings are followed up with discussion and probing (or does that maybe occur during or before the drawing process)? Are you using the drawings as part of an ethnographic study (i.e. documentation) or/and as a way for students to transform themselves and their world. Purpose needs to be considered here as well when we discuss audiencing. You can be your own audience, your family and friends and classmates can be your audience, and, especially if you are using digital media (going back to Dahlia’s comment about form), then the world can be your audience. As Rose points out, evocation is mediated by a million conditions and you can’t predict what a drawing will evoke to others (especially others not like you). In a brilliant book by Susan Sontag (Regarding the pain of others), she points out that images of dead Vietnamese evoked very different feelings from the Vietnamese and from American soldiers.

Dahlia raises an important question about the effects of an adult researcher choosing an arts-based research method to use with children. Luis also raises the question of ethics in research. If we work with children, we want to be always aware of how we manipulate the research process even when we claim to be fully participatory. In my own work, I worry about exploitation a great deal. We will be definitely discussing research ethics throughout the semester; though it will be front and center in some of my work, it will certainly be present in the work of others as well So it’s something I hope we continue to discuss.

Dahlia also cites LeGuinn’s idea that whole always seems beautiful and Muir’s idea that everything is connected. Hegel famously said, “the truth is the whole.” It all depends though from where you look and who is doing the looking. Sometimes the part is a whole in itself, the parts more complicated than the sum of them. And so scale is really important even while embracing the idea that we all, together (along with all other living and non-living things) comprise the universe.

I look forward to continuing the discussion tomorrow as we look at some videos together.

Thanks so much to all of you. I’m sure there is much you wrote that I did not properly address. If I’ve misrepresented any of you, please make that clear in class.

Gene