hooks, bell (1992). Black Looks: Race and Representation , Boston: South End Press. 115-31

hooks’ essay is an inducement to challenge and subvert a black imagery in America that she believes perpetuates, in black identity, an exploitive and immanently harmful status quo. So how is this done? I’m not sure.

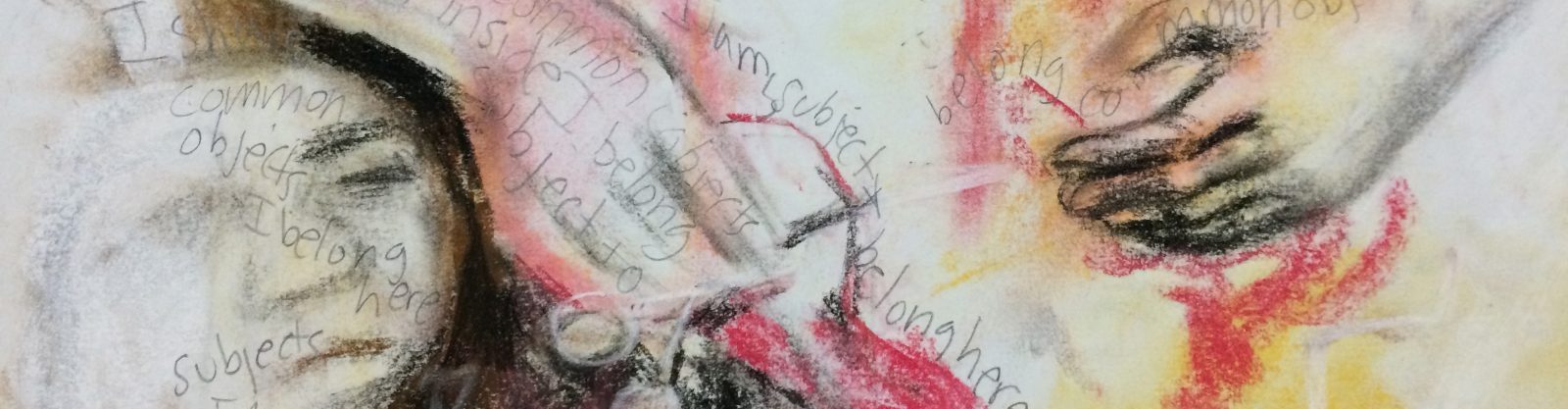

The essays, hooks asserts, are…”gestures of defiance” (4). But I think, and she later asserts, that art can play a role that is more than mere challenge, resistance, or defiance, all of which I believe are terms that are essentially reactive, even passive—since they still have the need to acknowledge a perceived outsider, dominant power against which action is necessarily directed. Why must we refer or even acknowledge any other power? A new creation that is transformative is not necessarily a reaction or resistance to any other perceived power or threat, as it can be likewise said that dominant power, where it exists, does not appear to acknowledge what it is dominating. hooks herself later affirms this in her essay ( I think mis-titled), “Oppositional Gaze,” in reference to the creation of radical black female subjectivity in film: a critical gaze by black female spectators will have to “… do more than resist. We create alternative texts that are not solely reactions“ (128). This is the creation that is truly transformative because of its independently conceived creation. Thus, revolutionary attitudes, the titular theme of her introduction, can be a creation wholly independent of any considerations of perceived domination or exploitation. She alludes to how such independently operating power may be instigated when she cautions, “…that little progress will be made if we transform images without shifting paradigms, changing perspectives, ways of looking”(4).

Yet, in this worthy pursuit, I think she slips back frequently into unhelpful tropes—that the root of much of this oppression lies in “white supremacist ideology,” or that white people cannot help but reproduce the imperial gaze of colonization and dehumanization (124). It may also not be realistic to think that any one person has the ability or the power to deliberately steer change in broader social perceptions towards a particular aim, that is, to “collectively change the way we look at ourselves and at the world [so] that we can change how we are seen”(6). Such utopian generalizations presume individuals can engineer perceptual changes of collective identity on the grand scale of the social, whose complexity no one will ever understand. It pulls focus from the imperative of each individual to work in their art on their own particular vision, for him or herself. Perhaps it may be sufficient unto itself, perhaps even for a lifetime, for any one individual to endeavor to accomplish this shift of paradigm, this change of perspective, in their own life. Art may offer that necessary means through the explorations of image, within this or any other theme, that reflect, refract, re-create paradigms of perceived reality for an individual.

In chapter 7, hooks asserts that existing film theory paradigms, whose visuals she asserts have been and continue to be in conformance to prescriptions of a dominant white, male perspective, reinforce a dominant male/female power dynamic that ignores race, and hence, disallows any radically subjective racialized perspectives. The woman inscribed in early film narrative is actually the white woman, a role later replaced by the black woman. “Woman” is the representation, not necessarily the “black woman.” The distinctness of the black woman’s reality is never represented. But this may be one consequence of who is making the art. As she aptly states in her later search for the black female perspective, “It is difficult to talk when no one is listening” (125).

Cole, Teju. (2018, May 24). What Does It Mean to Look at This? The New York Times Magazine.

Like the “brilliant skepticism” initially exercised by Susan Sontag in her work, “On the Pain of Others,” as the art scholar Susie Linfield characterized it, I am skeptical too about the value and aim of photography of human subjects as “objects,” and especially of that depicting human suffering. I would disagree with Sontag’s later relaxation in her stance, that “There’s nothing wrong with standing back and thinking.” I think there is something wrong with it. Beneath every stance taken in representing another person is a moral conundrum, and I find that conundrum in nearly all qualitative research of human subjects: there is always a cost and it is hard to pin down when it is often unrecognized, its danger compounded by its subtlety. In particular, images of suffering, as both Sontag and Linfield observe, position any viewer of that work, however moved emotionally, as separated consumers of an image whose evocation and effect on the viewer the human subject may not have intended nor given consent to. In today’s media-saturated ethos, were it not for the discernment of the journalistic profession, seldom would consumers concur that there exist images that no one has the right to ever see.

On the other hand, art that respects the complexity of its ethical and moral dimensions may the sine qua non of any transcendent art. For instance, art freely created by the subject is obviously created with the full consent of the artist, who consciously creates with the intention of sharing, welcoming the range of possible impressions upon, and interpretations by, viewers. Art created with subjects, which arts-based research can at times employ, does require researcher care in the ways of interacting with subjects that preserves the ethical and moral integrity of all participants.