Hi all:

I thought Luis presented a very thoughtful critique of hooks’ text. He criticizes hooks’ oppositional gaze as necessarily being defined by the dominant gaze, and thus necessarily dependant on it in a way he finds oppressive. Luis acknowledges that hooks also promotes the idea of “alternative texts that are not solely reactions,” and that these creation have the power to transform because “of its independently conceived creation,” but doesn’t the very term alternative also imply an opposition to an already established vision? Dahlia wrote, “our dreams and schemes are still informed and shaped by who we are now and the contexts in which we live.” We can’t escape the dominant lens entirely, but I think Luis’s point, and Dahlia’s as well, is that the act of creating itself can lead to transformation and new possibilities – new ways of thinking about ourselves – even if they are colored by visions that circulate hegemonically.

Luis and Dahlia both talk about how to create transformative artwork that creates new visions of possibility and identity, and Lamar adds to this discussion by asking, “How can I enhance my freedom dreams project to join this process in which people will see our Black and Brown children with new eyes, eyes of love, care, beauty, and humanity?” Luis answers quoting hooks, “We create alternative texts that are not solely reactions“ (128). Is it possible to erase from oneself all the deficit images of black and brown people that are constantly bombarding us in order to create alternative liberatory visions totally free of dominant ones? What questions should Lamar ask his students to facilitate the creation of such images? Lamar asks, “Do/Can freedom dreams convey parts of our cultural identities? Our history of struggles? Are elementary school children too young to have identities that are names to give to the different ways they are positioned by, and positioned themselves within?” His very question implies the burden and possibilities that history and domination necessarily play in the forging of identity and the pervasiveness of stigma and self-stigma, though it also opens up the door to Dahlia’s idea of becoming and the fluidity of identity. Lamar focuses on how “people will see our Black and Brown children” but he also has to contend with how black and brown children see themselves, which is a subject he raised in previous posts. Under what conditions can children making art re-paint their self-image and possibilities? This would be “art as research” and might align with Luis’s idea of art created with the subjects though the nature of that “with” is complex.

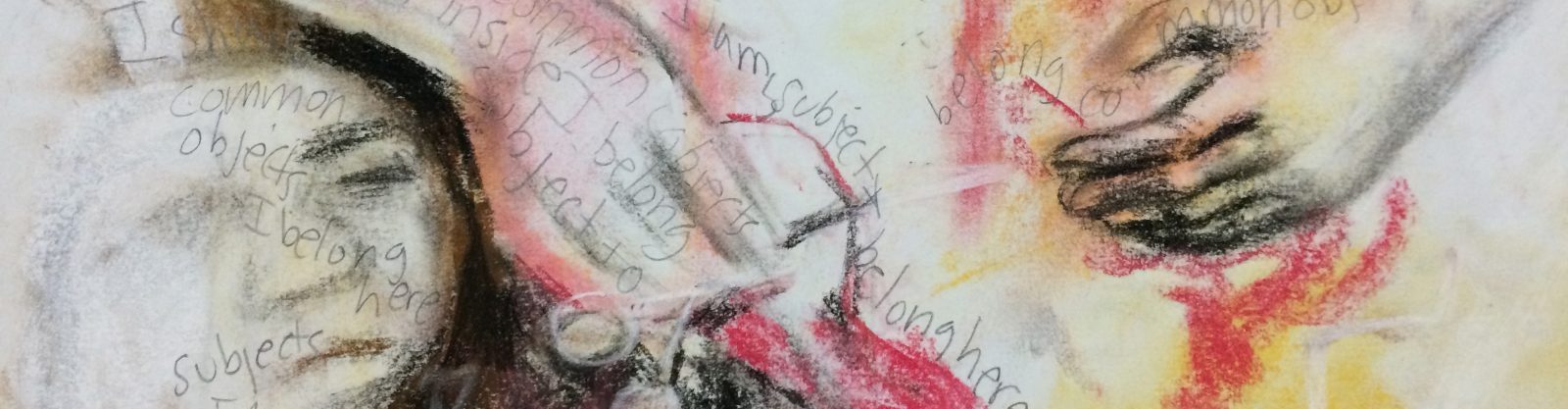

I wonder how all these ideas intersect with Greg’s project, “I hope to guide and help produce a diverse and representative study through contemporary portraiture, where agency is in the hands of the subject and the narrative is their own.” How is this going to work? Will you ask individuals to take selfies and then also to frame the context in which the selifes are seen (though obviously the audience context cannot be predetermined). In the images you uploaded, is agency in the hands of the subjects? What do we know about the women who are pictured? What then is the role of the researcher and, in particular, what is your role? When is the race of the researcher important (some great black literature has been uncovered and framed by white researchers but maybe, necessarily, the narratives of some one like Jill Lepore, Eric Foner and Howard Zinn are different than those of Saidiya Hartman).

Indeed problematizing the role of the researcher is a common theme throughout the posts as it should be given our goals this semester. Luis takes a strong and an uncompromising stance, “I think there is something wrong with it [standing back and thinking”] and he is clear, “there is a moral conundrum… in nearly all qualitative research with human subjects.” He proposes “art created with [my italics] subjects” but recognizes how careful a researcher must be to do it well. Do we think then that being a researcher who works with human beings is a necessarily compromised and untenable profession? Are we more righteous if we refuse to take the photo than if we take it, if we refuse to write the article rather than write it. If taking a photo of suffering, or writing an article about it, is necessarily complicit with the suffering itself and exploitative, what are our roles as scholars and thinkers? Can we give others voice without our voice being present at all and, if we could, would that be a good thing? How do the photos that Lamar took in DR and posted qualify as research and how does his commentary change how we see the photos? Incidentally, I was recently in DR as well in a place filled with American Blacks, Africans, and Europeans of all sorts and felt the staff of the resort were treated terribly by everyone; what does that say about hegemony and class and racial politics?

Liberation, as many writers, scholars and artists have said (see Baldwin for example) cannot be given. Dahlia’s caution about thinking of ourselves as saviors, or even the possibility of being a savior, strikes a chord in this regard as does Luis’ skepticism of what researchers can do. It is interesting that Dahlia’s paragraph about savior-ness ends with a sentence in which she, collectively, is the subject, “Unless WE transform images of blackness… WE cannot make radical interventions that will alter OUR situation” even as Dahlia’s identity in the US is often read ambiguously. In the language she uses, she implicitly rejects that others can liberate her and her people or provide alternate images, which is probably what Luis is saying as well. But being a researcher is already a privileged position, and the moral quandaries that attach to that position are multiple even when you identify as part of the people you are serving.

Finally, having a vision of justice and liberation implies that you think you are enlightened. Reading Freire’s Pedagogy of the oppressed, it seems clear to me that much as he writes about listening to the people and helping them to problematize their situation in their own words and based on their own experiences, there is the belief that if the people follow Freire’s pedagogy they will come to the same beliefs about liberation and justice as Freire has himself. Don’t we all believe this on some level? How can we be humble, good listeners, and good guides without being dogmatic and ideological? How do our own visions of the world and hopes for that world find nourishment and growth in the visions of those we work with so that we also continue to become and become enlightened?