I have to admit that I had so many feelings pop up while reading the pieces for this week.

I was excited to see how a range of different art forms from poetry to photography to collage to pop up books were used to help showcase the knowledge that kids already brought with them to school. From Paule Marshall’s love letter to the women in her life, to her childhood and to language to the Club Kids crafting magazines, there was a sense of love and honoring of kids. I loved the project where kids created pop up books that connected their own lives to those of famous changemakers because this idea of understanding the dialogue between now and then, between us and them, between what lives in history books and the ordinary moments of our lives is so crucial and yet so rarely touched upon.

But there were a few moments that made me pause. For example, in the piece Learning to Swim in Michigan, Craig Hinshaw writes, ” After reading their books I saw these immigrants to Hiller School in a new and more understanding way. It became clear to me how much all parents want the best for their children.” Part of me wanted to scream. Scratch that. All of me wanted to scream!

Why wasn’t this the assumption of the teacher before starting the project? Why did it take a whole bookmaking project for them to see immigrant parents as holding the same love and hopes for their kids? How could he possibly not recognize that when parents immigrate and sacrifice so much to come to another country, the well-being of their kids is what is on their minds? Why did they need to prove their worth to this teacher? Why wasn’t there the presumption of being a parent who cared?

Clearly the attitude of this teacher – Craig Hinshaw – infuriated me. But then I paused again and realized that maybe I was living in an idealistic lala-land where people actually valued other human beings and gave them the same benefit of the doubt they gave people “like them.” Craig Hinshaw is not unlike many teachers with whom I have worked in NYC – teachers who need evidence of their students’ (and their families’) humanity.

So…since we do live in this world…the importance of combining the arts with the lived experiences of our students feels so much more important. I take this for granted because I have been (oh so) privileged to have attended and taught in schools that saw the diversity of their students as a source of wealth for the schools. That used personal narratives and family histories as a way to create lessons and murals and celebrations. That brought in families as partners.

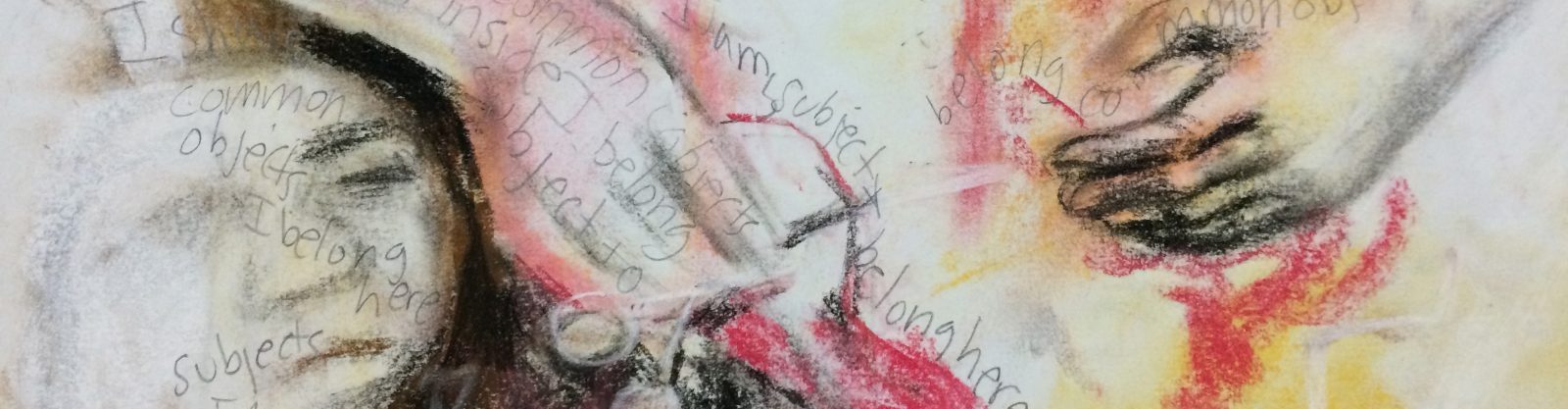

But I know that this is not the norm, as Robert Shreefter points out in the Borders/Fronteras piece. After all, the big project of American public schools, from the beginning, was to erase the language and culture and heritage of the students who came in in order to Americanize them. So, of course, kids are often taught that school is not a place where their stories belong. What intrigued me about this article was the sense of honor that both the students and the art was given. Their stories were taken seriously and lifted and honored. And art was a way to slow down, to really think through different elements of their experiences from the landscapes of Mexico to their interior landscapes. And then to think through the different artistic elements that could help convey the depth of these emotions. Art was not relegated to the role of just documenting experiences, but was, instead, used to help process and construct the understandings the kids had of themselves and their surroundings.

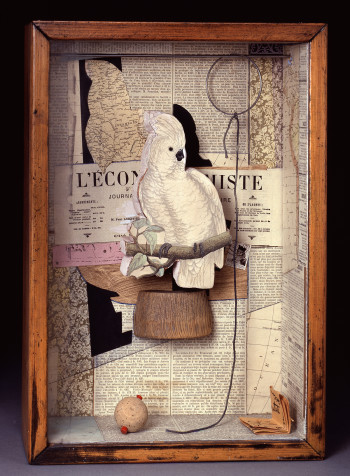

This is an idea I want to continue thinking through – and playing with…how do we think of art was a way to see things? I am starting to now see that the way I understand collage (thanks to scholar-artists like Gene and Victoria) is not just as a product or even a process but as a stance. As a way of being intentional about the messiness, the layers, the overlaps of life.