I enjoyed the readings for this week and they provided a powerful through line to my interest in collage and the relational and affective process of making art and narrating intergenerational experiences of black women and girls. Reading the article on photovoice and the collaging of young pregnant women left me wondering what it would like to place those processes in dialogue with each other for my class project? What if the girls and women took photos of their worlds while inserting the imaginary, natural, media images? How might this shift the dialogue in the space and on the paper? While thinking of the origin of photography and bodies specifically in the historical lives of black women and girls, I think of photos as violent exploitation, specifically pornographic voyeurism of white male social scientists. Further, I am reminded of Sara Baartman, and how black women and girl’s bodies were placed on display for inspection, exploitation and economic gain. I am brought back to this when thinking of the “immense danger associated with changing bodies and blossoming female sexuality” (54) and Anne Cheng’s assertion that “we don’t know enough about how racialized people as complex psychical beings deal with the objecthood thrust upon them…within the reductive notion of “internalization” lies a world of relations that is as much about surviving grief as embodying it.”(20) I wonder about this as I read the dialogue of the girls as they focus in and question each other’s physical characteristics and representation at various levels. I wonder about the interplay of time space in collaborative seeing? I wonder about how “the complex evocation of the children’s images and their context-dependent meaning can be preserved” within a photo, conversation, in the emotive registers and “embodied practices” (182) in the process of viewing and creating within intersectional black girlhoods? In this, I am also drawn to the “unknown girl.” I am curious about taking a critical bifocal lens and asking what part of her being unknown and thus separating herself is also a matter of social scientific research machine (Moynihan and others) that profits from the invention of a blackness and femaleness that represents and creates pathologies of poverty, pregnancy and violence while silencing the broader experience of poor white Americans? How white hegemony continues to obscure the material realities of generations of poor white folks and is also complicit in differing forms of racial exclusion inside and out of schools?

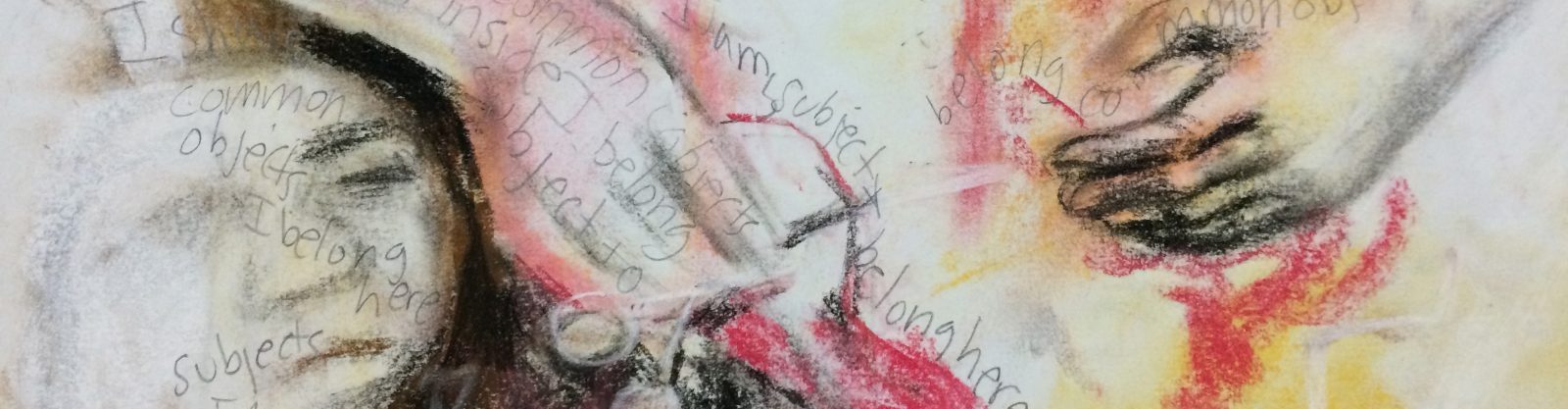

I also was thinking about how my own collage processing, where my human shape is never present but always reflected in a flow of ideas, colors and words. These readings also spoke to my role as an educator, who employs collage work regularly, and had me pause on the importance of prompts in art making. I am drawn back to Carol Gilligan’s push on the importance of offering an interviewee a real question, that is simple in its humanity and from a deeply mined place. A prompt must hold such complex simplicity as they provide a landscape for a certain type of exploration. I would love to learn more about the development of prompts for art-based research. For example, I am processing what it means to create a self-portrait versus a prompt to build a collage where you ask who am I? I loved the critical approach to collage making and centering the psychological associative logic that offers several pathways to interpretation and reinterpretation. I continued to think about the balance of being “glamourous” and that of a social justice art-based researcher and the constant anxieties that are produced in the process of trying to intercept hegemony, socially and psychologically and also create a space to be respected and safe. I appreciated how Luttrell weaves in her own narrative and emotionality in the process alongside the students. I am curious about, moments that she didn’t share in the article. If so, what were the other moments and how did she make the choice as to what to include? I am reminded of Kaela’s decision to paste a bright sun over her visit to the store. Where she clips and adjust her experience and what will be told in a purposeful manner. I was most blown away by the power of reading and viewing the teen’s reflexivity, curiosity and chatter as a heuristic for dialogic research processes. It is not the final result but the learning and growing that holds my attention throughout. I see this also reflected in Luttrell’s language, while sharing openly that much has changed in her own research over time and I also notice how the writing leaves gaps for curiosity and questioning. I appreciated the critical attention to power in the lives of children/people in the process of research and how tools, photography in this case, no matter how well intentioned is complicit in various forms of oppression. In response, I saw Luttrell speak back against simple first impressions and research that stand to further misrepresent the children, young women and families just as we saw Gabriel and Kendra share counter narratives in their photovoice projects.

I was also drawn to the “emotional landscapes” and the children’s and teen’s desire for “comfort, sense of belonging and respect”. I am curious about how Luttrell built her art research space? What did it look like? What sensory dynamics were important for her? I noted the use of “contraband” light music upon the young women’s request. This process of “homeplace” making called me to reflect on last Friday where I took my students on visual tour of three different spaces at NYU, one specifically on spatial precarity and another on sanctuary. PELEA: Visual Responses to Spatial Precarity https://wp.nyu.edu/latinxproject/event/pelea-visual-responses-to-spatial-precarity/, We Imagine Sanctuary: A Mural and Sound Installation http://apa.nyu.edu/we-imagine-sanctuary-a-mural-and-sound-installation-monday-february-25-friday-may-10-2019/ and Fritz Ascher: expressionist| Metamorphoses: Ovid Accoring to Wally Reinhardt https://greyartgallery.nyu.edu/exhibition/fritz-ascher-and-wally-reinhardt/

The youth’s emotive responses in each space were powerful and very diverse. PELEA students had a sense of feeling welcomed by the curator artist, warm feelings of familiarity, curiosity of whether racism was happening, beauty, nervous laughter and silence. The Sanctuary space slowed our pace, as we heard the audio recording share that “home is where my mother is” and other dreams and critical push towards survival in highly oppressed social positions. We sat in relaxed positions on the ground in the dimly lit space and named the place a sanctuary and wrote different ideas of peace “felt like grass with no wind. Just sun.” Students asked about the cost and the originality of a painting in the Fritz Ascher gallery. One student recently migrating from Chicago reinterpreted his expressionist flowers as explosions. Another poured over a book of poetry on a chair and another took a picture next to a sunset with a smile, stating this was her favorite. I am still processing the experience – as a sensory editing and remaking of visual art space – that takes on a sensory and dialogic component.